Chapter 30 - Closing the Residential Transaction

Learning Objectives

At the completion of this chapter, students will be able to do the following:

1) Explain the importance of marketable title.

2) Explain the difference between debits and credits.

3) Provide at least two examples of a prorated item.

4) List at least one credit the seller may receive at closing.

30.1 Closing the Property vs. Closing the Loan

Transcript

Closing is the day you will work towards in every transaction. At closing, parties to a real estate transaction connect all the loose threads. Buyers sign loan documents. Sellers sign deeds. Buyers receive new house keys. Sellers turn their property into cash. Lenders make it all possible by becoming long-term partners with buyers. Sellers, lawyers, closing agents, title insurers, and real estate agents are paid. Usually, everyone’s happy.

Ok, you might say, “That sounds nice but vague. What actually happens at closing and why is it so important?”

Let’s clear up the mystery with a story.

Imagine Gertrude wants to sell her house and hires Tom as her agent. They list Gertrude’s house for $300,000. If the house sells at that price, Tom’s brokerage firm will earn $18,000 in commission. Agent Tom finds Cynthia, who loves Gertrude’s house. Gertrude and Cynthia sign a purchase contract spelling out the terms of their deal. However, Cynthia only has $31,000 in cash. She has to borrow some money—actually, a lot of money—to buy Gertrude’s house. Who will lend Cynthia the $269,000 she doesn’t have?

Borrowmoney Bank will lend Cynthia $269,000. Cynthia’s credit is good, and she has a steady income. However, Borrowmoney Bank wants some things in exchange. Borrowmoney wants Cynthia to pay interest on the loan and it wants protection if Cynthia doesn’t repay the money. To get this protection, Borrowmoney Bank wants Cynthia to sign a promissory note and a mortgage deed. The mortgage deed will give Borrowmoney a powerful legal right called foreclosure. If Cynthia stops paying her loan payments, the mortgage deed allows Borrowmoney to take possession of Cynthia’s house, sell it, and repay the loan from the proceeds. Foreclosure is an awesome power for Borrowmoney Bank to hold over Cynthia, but without Borrowmoney’s loan, Cynthia wouldn’t have a chance of buying Gertrude’s house. She’s happy to have that chance, so she’s willing to give Borrowmoney that power.

So, let’s review the situation: Gertrude wants $300,000 for her house. Cynthia wants Borrowmoney to lend her $269,000 so she can buy Gertrude’s house. Borrowmoney Bank wants Cynthia to agree to repay her loan with interest and to give Borrowmoney the right to foreclose if she doesn’t pay.

At closing, the parties resolve all their nested needs, by signing all the paperwork necessary to finalize these transactions. Cynthia will sign the promissory note and the mortgage deed protecting Borrowmoney’s interests in the loan and the property. Borrowmoney will issue the checks giving Cynthia $269,000. After Borrowmoney gives Cynthia the money, Cynthia can cut her own check to Gertrude for $300,000. Finally, Gertrude will sign a deed transferring legal title of the house from Gertrude to Cynthia. And, of course, Gertrude will cut a check for Agent Tom’s commission.

Notice there are two big steps to this closing. The money must come first. There are some cash transactions in real estate, but they are rare. Usually, a lender is involved, and the buyer must close on the loan agreement with her lender first to get the money she needs to buy the house. Then—and only then—can the buyer and the seller close on their purchase contract. First comes the closing on the loan; then comes the closing on the property. The entire transaction will only complete when the buyer has the money to fulfill the purchase contract.

At any closing—not just Cynthia and Gertrude’s—the buyer and seller have different concerns. The buyer wants to make sure that the seller can convey clear title to the property. Does the seller have a mortgage of her own which the seller needs to discharge? Has a contractor placed a lien on the property for a home repair which the seller hasn’t paid for? If so, the buyer needs to know that the seller has cleared up these clouds on the title.

The buyer also needs to know that she’ll receive a valid deed for the property. Does the deed properly describe the property that she’s buying? Will the deed provide clear transfer of title from the seller to the buyer? The buyer’s lawyer will have to review the deed to make sure it’s legally sufficient.

The buyer also wants to make sure the property’s condition hasn’t changed for the worse, since she signed the contract. She needs to know that all inspections have been finished, and, if the purchase contract required repairs, that the seller has completed the repairs. The best way to make sure these things happened is to do a final walk-through or inspection, just before the closing.

Finally, the buyer needs to know that the lender has approved her loan and that the money is actually available at the closing. Everyone who needs to be paid—the seller, the lawyers, the title insurer, or the agent—needs to be paid.

The lender’s concerns overlap with the buyer’s in many ways. Like the buyer, the lender needs to know that clear title to the property exists and that the seller is conveying the title with a valid deed. In addition, the lender needs to know it has protected its future interest in the property with a binding mortgage deed.

The seller’s concerns are usually the simplest. The seller needs to know that the buyer has enough money to pay for the property and fulfill the purchase contract.

The closing affects the interests of many other people as well—title insurers, lawyers, closing agents, government regulators, and real estate agents, to name a few. We’ll talk about these interests in later lessons. For now, it’s enough to know that closing is that magical place and time when the parties address and resolve all their unresolved interests and concerns. Usually, they do this first by closing the loan and then by closing the sale. Most of these concerns are resolved through documents like title reports, settlement statements, warranty deeds, mortgage deeds, and checks. We’ll discuss all these topics and more in the lessons ahead, and by the time you finish this chapter, the closing process will no longer feel like a mystery.

Key Terms

Closing

A written agreement or contract between seller and purchaser in which they reach a “meeting of mind” on the terms and conditions of the sale. The parties concur; are in harmonious opinion.

30.2 Title Procedures

Transcript

Let’s talk title. We often say that a property owner holds a “bundle of rights” to the property. This bundle includes rights such as the right to possess the property, to use the property, to lease the property to another person, and to sell the property. Title refers to ownership of this bundle of rights.

A property owner can separate the rights in the bundle. An owner can rent the right to use the property by leasing it to a tenant. A landowner can sell the development rights for his property and place the property into conservation. With the lease, the owner expects the conveyance will be temporary; with the conservation, the owner hopes it will be permanent. In both instances, the owner keeps all the other rights in the bundle, even though the owner has given away one right. With so many potential rights-holders in real property, we need a way to identify owners and find out whether a property owner has conveyed any of the rights in his bundle to anyone else. Our title system is the way we keep track of these property interests.

Imagine I took a watch off my wrist, held it out to you, and offered to sell it to you for $50. If you were interested in buying the watch, how would you know I owned it? What could I show you to prove I had the right to sell the watch? If I show you a receipt from a store, how would you know that receipt was for the particular watch I was dangling in front of you? How would you know the receipt was even real, if it came from a store you didn’t know?

In the case of a watch, you might let the whole ownership question slide. I have the watch. You can take the watch from me right now, in exchange for $50. You can examine the watch closely and judge its quality directly. The watch is portable, and it’s inexpensive. Once we part company, you’ll get to keep the watch. Given all these circumstances, you might overlook ownership concerns and just take me up on my offer.

That doesn’t work for real property. Real property is expensive. So expensive, you’ll probably have to borrow money from a lender to buy it. And you can’t move real property. If you buy a house, you want to know that no one is going to unlock the door someday, walk in, look at you, and demand, “What are you doing in my house?” Your lender wants to make sure this surprise doesn’t happen, too. The lender lends you money because it believes you are buying the property from the owner and that you will own the property after closing. Both lender and buyer want proof that the seller who shows up at closing actually has the legal right to sell the property.

This is where the ideas of title and marketable title come in. We designed our title system to make sure that everyone involved—buyers, lenders, and the world at large—can easily identify the owner of a property and identify anyone other than the owner who holds a significant interest in the property.

In the United States, we keep all the records of conveyances involving real property in local land record offices. The local officials who maintain these records go by different names—town clerks, county recorders, county clerks—but they all serve the same function. They record and document transactions that affect title to real property located in their area, be it town, county, or district. Warranty deeds, quitclaim deeds, mortgage deeds, liens, tax delinquencies, zoning permits, land use permits—anything that might affect the bundle of rights that make up the title to a piece of real property can be recorded in the land records.

Because each land record office maintains records for properties located within a particular geographic boundary—a town, a county, a region—the land records affecting title to a particular property are located mostly in a single office. A person who wants to know who owns a particular property can find out who by visiting a single land records office. Now, we keep some records that affect title elsewhere. For example, we sometimes store state regulatory permits in a state agency’s office. Even in that case, someone usually records a brief notice in the land records stating that relevant records exist somewhere else. This system of one-stop shopping helps keep title to real property easily discoverable.

The courts support the title system. In resolving disputes about ownership of real property, courts presume the record owner identified in the land records is the legal owner of a particular property. Anyone who wants to overcome that presumption must present strong evidence explaining why the presumption should be set aside. Because the legal system strongly favors the rights of those with recorded interests, a buyer wants to make sure that the land records identify the seller as the owner before the closing occurs. Specifically, the buyer wants to know the seller can convey “marketable title.”

MARKETABLE TITLE

The exact definition of marketable title varies by state and the local definition always controls the meaning. But the central idea is this: Marketable title exists if the land records show that the seller owns the property and that the seller can convey the property free of any significant claims, encumbrances, or liens by third parties.

Marketable title does not mean that a property is free of all claims, encumbrances, or liens. For example, many properties are subject to third party interests that do not affect the marketability of title. A power company might have the right to run power lines across a section of property. A neighbor might have the right to draw water from a property well. A neighbor might have the right to cross use a driveway to reach his own property. Interests like these usually do not affect the marketability of title because they don’t unreasonably hinder the buyer’s use of the property and would not prevent the buyer from selling the property later.

The interests or claims we care about are claims that would prevent the buyer from selling the property later, or claims that do threaten the buyer’s use of the land that no reasonable buyer would accept the title with that claim hanging over it. One common claim that would render title unmarketable is a mortgage. If the seller owes money to a lender, and the lender holds a mortgage deed on the property, most buyers will not accept title unless the seller pays off the loan at closing and the lender discharges the mortgage. If the buyer takes title subject to the mortgage, and the seller does not pay off the loan, then the lender could foreclose on the property and sell the house from under the buyer. Before the sale closes, the buyer is going to want the seller to prove that he paid the loan and that the lender will discharge the mortgage. The buyer’s lender is also going to insist on proof that marketable title exists.

So, how do the buyer and lender know whether marketable title exists? Someone—usually a lawyer, a paralegal, or a title examiner—will search the land records for them to find out whether the seller holds title and whether the records contain any third-party claims against the property. The title searcher will look for any document in the land records that affect title to the property—deeds, liens, easements, mortgages, leases—anything. State law usually requires this title search to cover some specified period—for example, the last 40 years.

Title examiners don’t just thumb through the land records, hoping to stumble across something relevant to the property. The records clerk indexes all the land records, either by the names of the people granting and receiving property interests or by the property itself. This indexing is the key to the title examiner’s search.

Let’s imagine that Wilbur lives in a state that indexes land records by the names of grantors and grantees. Wilbur is selling his house to Olivia, and Olivia asks Jane to search Wilbur’s title. Jane begins by searching the index for every record that involves Wilbur. If Wilbur has a mortgage, Jane makes a note of the mortgage. If the town recorded a tax delinquency notice because Wilbert didn’t pay his property taxes, Jane makes a note of the delinquency. She does this for every record involving Wilbur. These items will affect the marketability of Wilbur’s title, and Wilbur will have to resolve them at, or before closing.

Then, Jane starts looking at the prior owners. By looking at the deed that gave Wilbur title, Jane learns that Wilbur bought the property from Eileen. Jane then searches the records for everything involving Eileen. Jane learns that Eileen bought the property from Heinrich, and Jane searchers the records for Heinrich, and so on and so on, until Jane has gone back through the records for the required period, looking for any title impairments and noting each person who sold and bought the property. As she works, Jane learns that Monty sold the property to Constance, Constance sold to Heinrich, Heinrich sold to Eileen, and Eileen sold to Wilbur. We call this trail of records, linking buyer to buyer to buyer, the chain of title. If the chain of title is unbroken—if each seller properly conveys title to the next buyer—and the records show no evidence that a third party holds a significant unresolved claim on the property, then we consider the title marketable.

As I said earlier, the presence of a live claim in the record, like an undischarged mortgage or a tax lien, can make a title unmarketable. But absences in the land records can affect marketability as well. For example, Wilbur would have a title problem if Jane found that Monty sold to Constance, Constance sold to Heinrich, Phillip sold to Eileen, and Eileen sold to Wilbur. What happened between Heinrich and Phillip? How did Phillip acquire the title Heinrich held? If the record does not explain this jump from Heinrich to Phillip, then Wilbur has a problem with his title. He has a “cloud” on his title.

A cloud on title is anything that casts doubt about a seller’s title. If a cloud on the title exists, the seller must clear up the issue before the sale can close. In Wilbur’s case, he must find the missing link connecting Heinrich and Phillip. Maybe Phillip forgot to record the deed from Heinrich to Phillip. To close, Wilbur (or his attorney) will have to find the missing deed, record it in the land records, and create an unbroken chain of title.

TITLE ABSTRACTS AND TITLE OPINIONS

After a title search, the title examiner provides a report on title to the buyer. This report might be an abstract of title, which is a summary of everything the examiner found in the land records affecting title—all the transfers, conveyances, legal proceedings, and other facts showing continuity of ownership and documenting any facts that might impair title. An attorney might also issue an opinion of title, which provides a legal opinion on whether title is marketable, based on all the records described in a title abstract. The attorney’s title opinion is not a guaranty of title—it is just the attorney’s judgment about whether marketable title exists, based on the evidence in the land records. An attorney giving a title opinion does not act as a guarantor or insurer of title.

TITLE INSURANCE

For that particular service, a buyer can purchase title insurance. Title insurance protects against the risk of title defects not evident from the land records. If someone appears after closing claiming they have an interest in the buyer’s property, the title insurer will pay the costs of defending the title, up to the amount of coverage, stated in the title insurance policy.

Title insurers usually issue title policies for buyers and lenders. For buyers, the title insurer defends claims that threaten the buyer’s title to the property or impair any of the rights in the buyer’s bundle of rights. For lenders, the title insurer defends claims that might affect the lender’s mortgage, like the claims of other lenders.

Title insurance, like most insurance, protects buyers and lenders against risk—in this case, the risk that a stranger will appear after the sale, claiming an interest in the property. Even if the title examiner searches the land records well and the attorney’s title opinion is sound, potential claims not clear from the record may still exist. Title insurance provides buyer and lender peace of mind that if such a claim appears, the title insurer will pay to defend the title.

Although our title system may seem complicated, it works quite well because it is self-correcting. Every buyer knows her property purchase will only be as secure as her title, so the buyer and her lender check title carefully before closing. If they find a title defect, they insist that the seller fix the defect before closing. Because the seller’s primary duty under a purchase contract is to convey marketable title, the seller usually moves quickly to fix any defect found. If the seller can’t cure the defect, then the buyer will walk away from the deal. Every time a sale occurs, the new buyer reexamines the title and a new title examiner searches the record. With so many motivated eyes looking at the title record, title defects do not last in the record for long. With a bit of luck, and a lot of title searching, a marketable title will always and ever shine down, clear and unclouded, on the closing table.

Key Terms

Chain of Title

A history of conveyances and encumbrances affecting the title from the time the original patent was granted, or as far back as records are available, used to determine how title came to be vested in current owner.

Abstract of Title

A summary or digest of all transfers, conveyances, legal proceedings, and any other facts relied on as evidence of title, showing continuity of ownership, together with any other elements of record which may impair title.

Marketable Title

Title which a reasonable purchaser, informed as to the facts and their legal importance and acting with reasonable care, would be willing and ought to accept.

Opinion of Title

An attorney’s written evaluation of the condition of the title to a parcel of land after examination of the abstract of title.

Title Insurance

Insurance to protect a real property owner or lender up to a specified amount against certain types of loss, e.g., defective or unmarketable title.

30.3 Contract to Closing

Transcript

The final step in the real estate purchase process is the closing, or settlement. At closing, the seller transfers title to the buyer and the buyer pays the seller the agreed upon purchase price. A licensee who understands the necessary procedures and documents and assists both the buyer and seller in the process leading up to the closing will help make for a productive and successful closing.

Both by law and by custom, the licensee continues to support the seller and the buyer through the day of closing. There are numerous duties a licensee has between contract and closing. Additional opportunities to assist the seller and buyer also typically arise during this timeframe.

After the Contract Is Signed

The licensee's involvement in a sales transaction falls into three phases: listing and marketing the property, assisting in the contract negotiations, and helping the parties complete the sale. Immediately upon the acceptance of the sales contract by all parties, the third phase begins.

When the parties have accepted and signed an offer to purchase, the licensee's first obligation is to deliver a complete signed copy of the purchase agreement to the buyer, the seller, and the broker(s). Neglecting this step is a violation of the license law.

Contingencies in a sales contract means that the parties do not have a binding contract unless and until the contingencies are met. Because a property remains tied up and unavailable for sale when a contingency in a contract exists, the licensee must immediately work to secure the appropriate action of the seller, buyer, or both to remove the contingency.

Note: A seller and new buyer can enter into a backup contract in the event the original contract falls through.

Example Contingencies

The financing contingency is probably the most common since most buyers need to obtain a mortgage to purchase property. Typically, a buyer must apply for the loan within a specified length of time or “promptly.” The licensee can help by urging the buyer to apply immediately and by offering information and assistance as appropriate within the constraints of BRRETA.

If it appears that the contract may be contingent upon the buyer's ability to assume the existing loan, the licensee should determine the lender's requirements for such application immediately after getting the listing so that the licensee can inform any prospective buyer of the required application at the time an offer is made.

If the contract is contingent upon a timely inspection of the property by a qualified home or building inspector, the licensee can assist the buyer by supplying a list of several qualified inspectors and by accompanying the buyer(s) to the property during the inspection.

If the contract is contingent upon a favorable appraisal, the licensee can facilitate the process by cooperating with the appraiser. That cooperation may mean anything from unlocking the house for the appraiser to supplying information on comparable sales to the appraiser.

If the contract is contingent upon the sale of the buyer's property, it is the licensee's responsibility to do all he or she can to assist the buyer in selling the property within the time specified in the contract. That may involve listing the buyer's property for sale if not already listed or referring the buyer to another broker if necessary; however, if the licensee lists the buyer's home, he or she must advise the seller in writing since such action may create conflicts of interest or even a dual agency.

Working with a Buyer If You Represent the Seller

As a listing agent, creating a positive rapport with a buyer is certainly acceptable; however, the licensee must remember that his or her legal responsibility is as an agent for the seller. BRRETA allows a licensee who represents one party to perform ministerial acts for the other party without becoming the other party's agent. Doing things such as choosing a lender or recommending a specific inspector may exceed the allowable scope and could create a conflict of interest with the seller. That may result in a violation of the law because the licensee is acting as an agent for both parties without their knowledge and consent.

If a buyer needs financing, the Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act (RESPA) limits the broker's role to making recommendations to the buyer. Ultimately, the buyer must choose which mortgage company to use. The licensee should, however, remind the buyer that the chosen lender should not require terms or fees that violate the terms of the contract. Common problem areas include discount points and closing costs, contractual obligations a seller may have with a construction lender regarding permanent financing of the property, and prepayment penalties on the seller's existing loan which the lender may waive if the new loan is placed with the same lender.

Working with a Seller If You Represent the Buyer

Conversely, a licensee may represent the buyer but work closely with the seller. The seller may be separately represented or be unrepresented in a FSBO (for sale by owner) sale. BRRETA requires certain duties from the licensee toward the party that the licensee does not represent. In this case, the licensee must treat the seller fairly, disclose to the seller all material adverse facts known to the licensee, and may not knowingly provide false information. Moreover, if the seller is unrepresented, the licensee must use extra care neither to imply that he or she is acting as the seller’s agent nor act publicly as if he or she represents the seller. Doing so could create an "accidental agency.”

A Listing Agent’s Duties to the Seller Prior to Closing

A licensee’s obligations to the seller continue beyond the acceptance of an offer to purchase. The licensee remains responsible for keeping the seller informed and assisting the seller to fulfill the terms of the contract until the transaction is closed.

The seller must be kept apprised of the progress of the buyer's loan application and approval. Specifically, the seller needs to know the following:

- Did the buyer make a loan application according to the terms specified in the contract, such as applying with a designated lender or applying within a designated time frame?

- Is the buyer making good faith efforts to comply with the terms of the contract by providing all necessary information to the lender?

- Has the property been appraised for the contract price, and is the lender requiring any repairs to the property?

- Has the lender approved the buyer for the loan? If not, knowing the reason for denying the loan may be helpful in the renegotiation of the contract.

A licensee is also responsible for assisting the seller in complying with all terms of the contract and dealing with additional issues that arise prior to closing. For example, a licensee may need to help locate the appropriate contractor if repairs are required. A licensee may also need to help a seller understand, and comply with, certification requirements within a contract regarding the absence of termites and other wood-destroying organisms. Finally, if the seller has agreed to provide home warranty insurance, the licensee is obligated to see that the seller complies with the steps necessary to satisfy that agreement.

Working with a Buyer Prior to Closing

Once a buyer has a signed contract and has applied for a loan, the licensee should, as a matter of good business practice, check on the status of that application at least weekly. In the event of a problem, the lender may ask the licensee for assistance in resolving the problem. For example, if the lender has not yet received the necessary documents, the licensee may need to call the buyer to get the documents delivered. If the appraisal came in below the contract price, the licensee may suggest alternatives and/or ask the lender to reconsider the appraisal if comparable sales in the area appear to warrant a higher value.

In addition, the licensee should remind the buyer of any other contingencies or stipulations that the buyer is responsible for and should monitor the buyer's progress in complying with them. For example, the licensee may need to ensure that the inspection takes place in a timely manner.

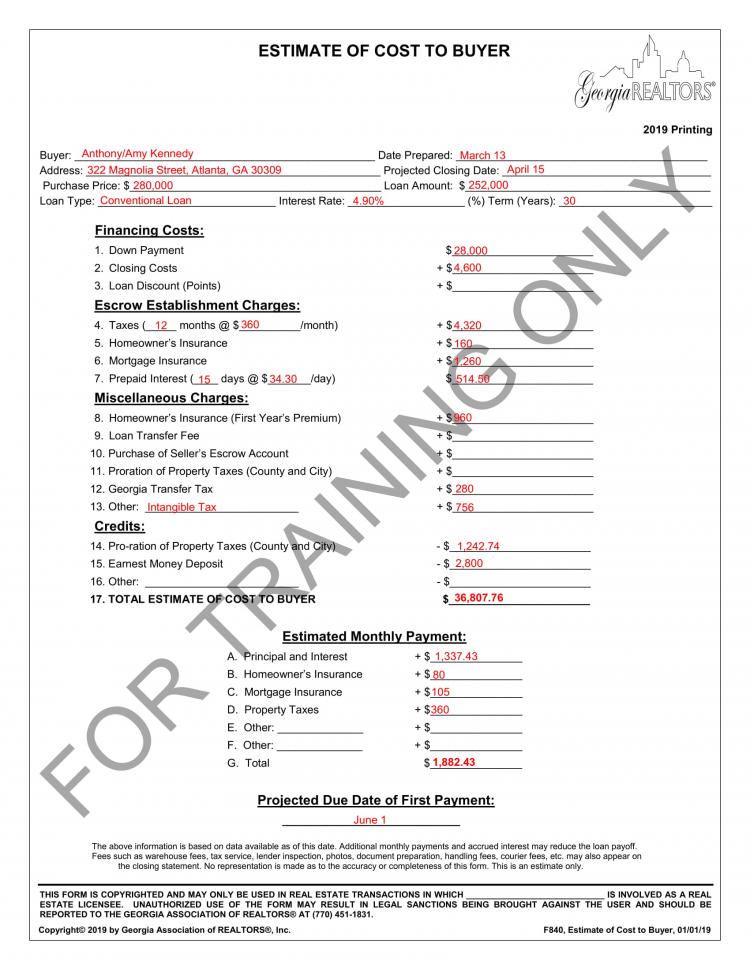

Furthermore, the licensee should help the buyer prepare for closing which usually entails making sure that the buyer has obtained sufficient funds to meet the buyer’s cash obligation. Georgia law may require certified funds or a wire transfer. If the purchase involves financing, the licensee should also make sure the buyer has obtained a hazard insurance policy prior to closing as well as explain to the buyer that the policy must include the lender as a loss payee (which is the party who receives the insurance proceeds for an insured loss). Because it can take several days to deliver an original insurance policy, a licensee should explain the need to obtain a policy well in advance of the closing.

Finally, a licensee is responsible for informing the buyer of any substantial changes in the property. For example, a buyer should be notified of a previously unknown defect, or of any new damage to the property, even though it may void the contract.

Working with the Closing Attorney

Georgia law requires a closing to be handled by an attorney who may represent the lender, the buyer, or the seller. There may also be other attorneys present at the closing representing the other parties. Nevertheless, a licensee may still need to provide assistance in several ways, starting with supplying information and documents. If the lender has not provided the attorney with a true copy of the sales contract, the licensee should do so. The licensee may also need to provide the lender's copy of the buyer's hazard insurance policy and a termite clearance letter, if required. Once the loan is approved, the licensee may need to facilitate the setting of a closing date, time, and place in accordance with the terms of the contract and taking into account the schedules of the attorney, buyer, seller, and agent.

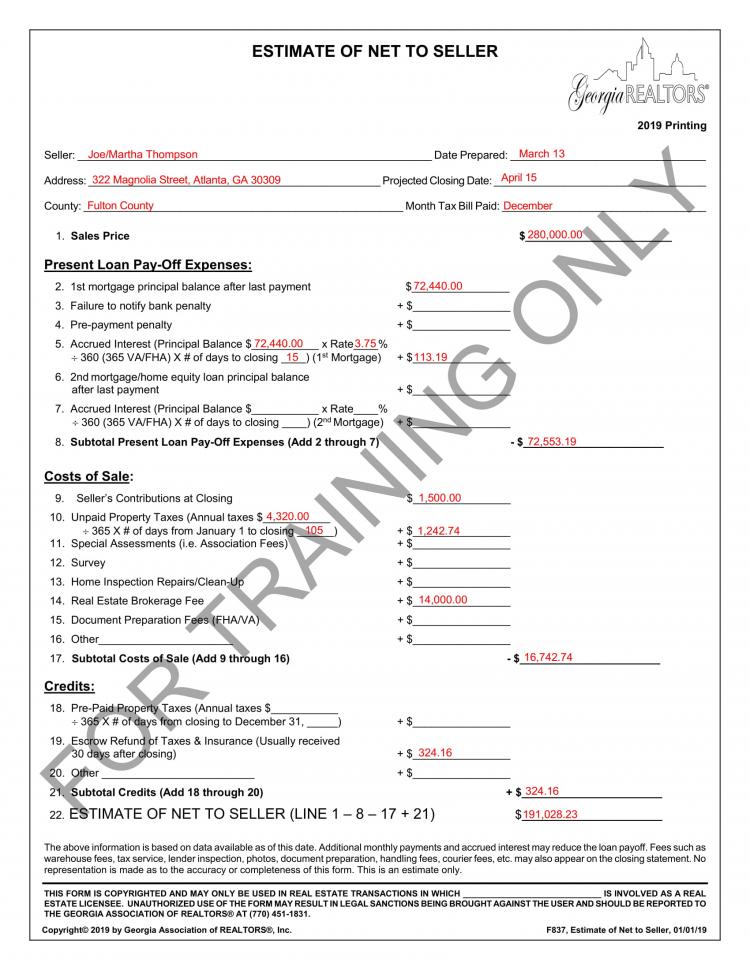

Finally, a licensee may need to inform the buyer and seller of what they need to bring as well as prepare them for what to expect at the closing. It behoves the licensee to show the parties sample forms and to explain what documents will be needed at closing. It is also recommended to provide the seller with an estimate of cash due and the buyer with the amount and type of funds he or she is required to bring at the closing.

The Broker’s Responsibilities in a Real Estate Closing

In Georgia, closings must be conducted by a licensed attorney who makes sure that all the documents are properly executed. The attorney delivers the deeds, notes, affidavits, and other documents to the proper parties, prepares the closing or settlement statement, and disburses the funds according to that statement. A broker cannot oversee any of these functions, nor may a broker prepare legal documents, under Georgia law. Nevertheless, a broker should still have a representative at the closing to complete its duties as agent for the client.

Each individual company decides whether the broker, or the sales associate that negotiated the transaction, will attend the closing. Whoever represents the real estate firm should verify that all the parties receive copies of the settlement statement, which is required by state law to be delivered by the attorney to the buyer and seller. The statement is delivered at the time of closing and must show all the receipts and disbursements handled by the closing attorney for the seller, and all money received in the transaction from the buyer, as well as the reason for and manner in which it was disbursed. If a sales associate attends a closing on behalf of the broker, the sales associate must secure a copy of the closing statement and give it to the broker.

If the broker is holding an earnest money deposit, arrangements should be made with the closing attorney for disbursing it. The closing attorney may insist that the broker bring the earnest money at closing as certified funds so that the attorney can deposit it in the attorney's escrow account and disburse it with all the other funds in the transaction. Alternatively, the broker may refund the earnest money to the buyer at closing by a check drawn upon the broker's trust account or retain the earnest money and apply it towards the broker’s commission, receiving the balance of the commission by check at closing.

What to Expect at the Closing Table

Typically, in a residential closing in Georgia, an attorney representing the lender will conduct the settlement. The attorney prepares the documents and explains each one to the buyer and seller as it comes to their turn to sign it. Remember, the attorney represents the lender, not the buyer or seller. Consequently, the attorney can explain the contents of documents, but cannot give the seller or the buyer legal advice. The parties may bring their own attorneys to the closing; however, most do not. Usually, the attorney explains each step of the process to help the parties understand what they are signing. If a licensee explains all costs to each party prior to closing, problems are less likely to arise during the closing.

In a commercial closing, both buyer and seller are typically represented by attorneys with one attorney having the primary responsibility for preparing the closing documents while the other attorney(s) reviews drafts of the closing documents prior to the closing. The broker generally plays a smaller role in guiding the parties through the transaction because the parties are typically more knowledgeable about real estate transactions.

Common Closing Documents

A warranty deed is the most common type of deed used to transfer title. Others that may be used include a quit claim deed, executor's deed, or trustee's deed. The seller signs the warranty deed, a notary public must notarize the deed, and an unofficial witness who is not a party to the transaction must sign for the deed to be recorded. The notary and the witness are usually employees of the closing attorney, although the attorney may ask the licensee to be a witness. The seller or attorney then hands the deed to the buyer and the seller has officially transferred title. It is standard practice for the attorney to keep the original warranty deed at closing for recording at the courthouse after which the original deed is mailed to the buyer.

If the buyer takes out a new loan, the lender will require execution of a security deed (also known as a "deed to secure debt" or "loan deed") which is used in Georgia instead of a mortgage. The security deed also transfers title and contains many of the same clauses as the warranty deed. Only the buyer signs the security deed which transfers title to the lender from the buyer but only for the purpose of securing the loan. The buyer/borrower retains the right to use the property as well as retains the burdens of ownership, such as the obligation to pay property taxes. The security deed must also be notarized and witnessed before being recorded.

The promissory note documents the buyer's (borrower's) promise to repay the amount of money borrowed and sets forth the terms under which the money is to be repaid (interest rate, monthly payment, number of payments) plus any special provisions, such as:

- A prepayment penalty charged on a conventional loan if the borrower pays off the loan before the due date. These penalties typically require payment of a percentage of the remaining principal balance of the loan if the loan is paid off earlier than a certain number of months or years after the loan is made.

- A late penalty which gives the lender the right to charge a fee if the borrower makes a payment after the due date.

- An escalation clause that gives the lender the right to increase the interest rate if a new buyer assumes the loan.

- An acceleration clause that gives the lender the right to call the entire loan balance due upon default.

These provisions may appear in the security deed, promissory note, or both. Only the borrower signs a promissory note which is not recorded.

A quit-claim deed may need to be signed before or at the closing. Quit-claim deeds are used extensively to remove from the record possible conflicting interests in property. For example, a quit-claim deed is used to correct an error in a previously recorded deed, relinquish a spouse’s interest in the property when the seller's divorce is pending, or to transfer title from an heir of a deceased prior owner. If the attorney shows the parties the quit-claim deed but does not ask them to sign, then the purpose is likely to show that someone else who had, or might have had, some interest in the property has released that interest so the title can be transferred free and clear. If the attorney has the seller sign, it releases a possible claim the seller might retain on the property. Also, these deeds are witnessed, notarized, and recorded.

An owner's affidavit is a document signed by the seller in which he or she swears there are no unpaid or unsatisfied liens, assessments, or encumbrances against the property other than those identified by the title search. The owner's affidavit protects the buyer, lender, and attorney because they can sue for damages if the seller lies in the affidavit. The owner's affidavit is notarized but not usually recorded.

A lender may require a buyer to sign a buyer’s affidavit in which he or she swears there are no lawsuits, judgments and current or pending liens against him or her. The buyer's affidavit assures the lender that the lender's loan has first priority and that there are no other claims on the borrower that might take precedence. The buyer's affidavit is also notarized but not usually recorded.

Other documents may also be required at closing, such as a survey, an occupancy affidavit, and a title policy as well as disclosures and disclaimers, a truth-in-lending statement, and various FHA or VA forms, if appropriate.

Key Terms

30.4 RESPA Requirements

Transcript

INTRODUCTION TO RESPA

We closed out the last lesson saying that although the closing table might accommodate many people, not all the stakeholders are present. The federal government also takes an interest in what happens at closing.

The federal government wants to make sure that buyers understand the terms of the loans they are undertaking. The federal government also wants to protect buyers from artificially inflated costs associated with the settlement of the sales transaction. A law called the Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act, or RESPA, is the mechanism that tries to achieve these two goals.

Let’s go over that acronym one more time, because we’ll be using it a lot in this lesson, and you’ll hear it a lot out in the wild. It pays to know what the acronym stands for. The title says it all: the Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act—it’s a law used in real estate–RE—to regulate settlement procedures—SP—and it’s an Act of Congress—A. RESPA!

Where did RESPA come from? Well, back in the early 1970’s, after lobbying by consumer groups, Congress grew concerned about certain lending practices in the real estate industry. At the time, lenders described their loans to consumers in many ways and included fees and other charges beyond the stated interest rate. As a result, consumers sometimes had difficulty understanding the loans or finding meaningful ways to compare loans offered by different lenders. In addition, some parties involved in the settlement process—title insurers and title searchers, among others—seemed to have special arrangements between themselves and with the lenders for referring business to one another. These arrangements included kickbacks between the parties. For example, if a lender recommended a certain title insurer, the title insurer might charge a higher rate than they normally would for title insurance, and send a portion of the overcharge back to the lender, in exchange for the referral. As a result, buyers sometimes wound end up paying more for services, from recommended providers, than they would pay someone else for the same service.

Congress wanted to make it easier for consumers to understand and compare loans and to prevent the kickbacks and unearned fees that resulted in higher closing costs. In 1974, Congress enacted RESPA to achieve these goals. Congress has amended RESPA many times, with the latest amendment coming after the 2008 housing crisis in the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act.

WHAT RESPA REQUIRES

RESPA applies to all “federally related mortgage loans.” As with any complex congressional act, a host of exceptions, exclusions, and special circumstances apply. In general, though, RESPA applies to any sale of a one-to-four family residence, which includes a loan by a commercial lender.

RESPA works by requiring lenders and/or mortgage brokers to give buyers a series of strictly timed disclosures about the loan and by imposing an enforcement scheme to prevent kickbacks and unearned fees. The enforcement scheme includes direct oversight by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) and indirect oversight through private law suits brought by individuals.

RESPA’s beating heart, from the perspective of the buyer, are the disclosure requirements. After a buyer submits a loan application, the lender has three days to give the buyer two items. The first item is an informational booklet called “Your home loan toolkit: A step-by-step guide.” The toolkit explains the costs associated with closing the loan. It explains things like title insurance, appraisals, and closing agents. The Toolkit also explains how mortgage loans work and helps the buyer understand how to shop for loans and figure out whether a loan will be affordable. RESPA suggests that the lender give this booklet to the buyer as early as possible. The lender must provide the booklet within three days of receiving the buyer’s loan application.

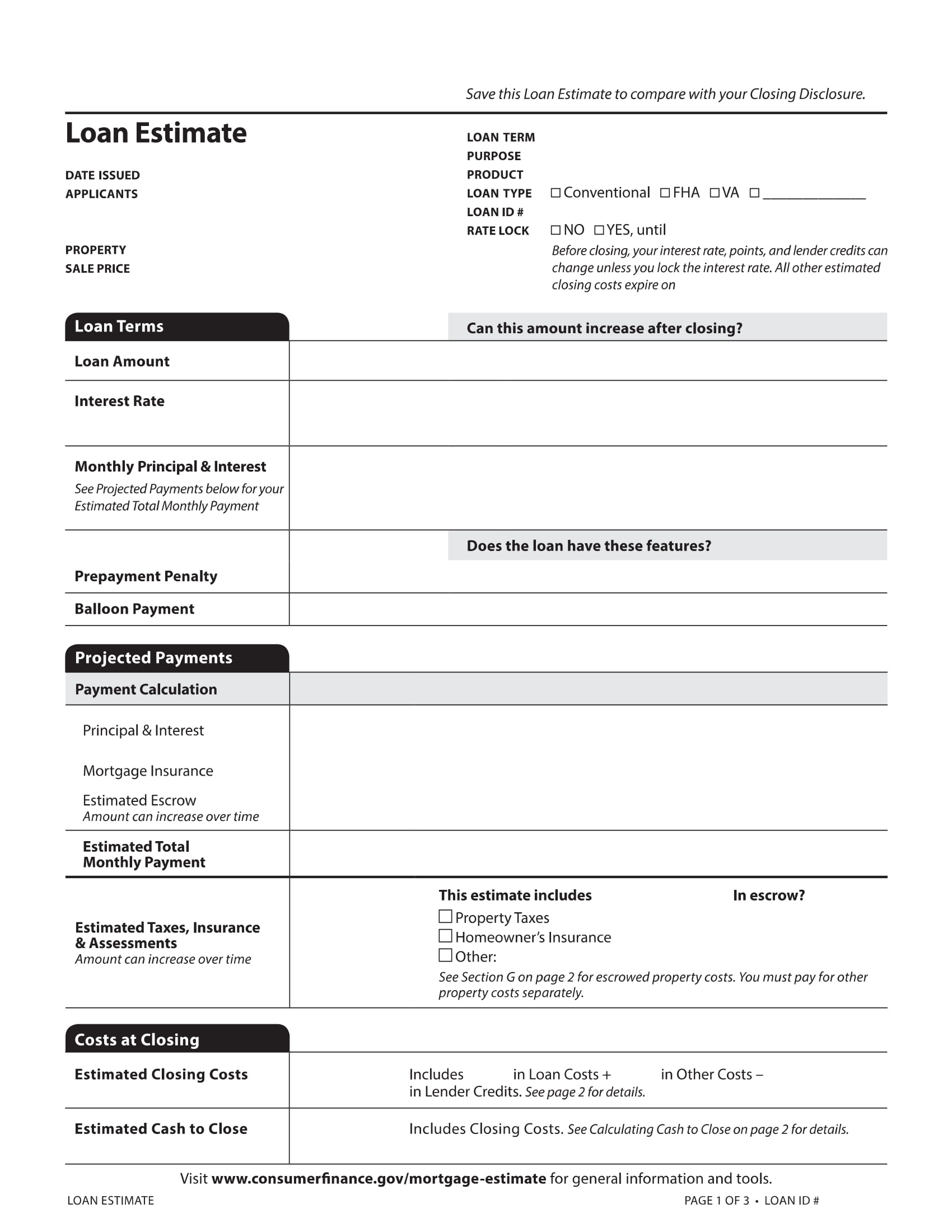

The second item the lender must give the buyer is a completed form called a Loan Estimate, or LE. This three-page form is highly structured, and every Loan Estimate has the same sections, laid out in the same order, providing the same kind of information. The only things that change are the names of the parties and the numbers associated with the loan and the sale. This uniformity of appearance makes it easy for a consumer to compare loans and settlement services. The buyer can compare apples to apples and oranges to oranges.

What’s on the Loan Estimate? The lender’s best good faith estimate of all the terms and costs associated both with the loan and with the closing.

The first page identifies the basic terms of the loan—the loan amount, the interest rate, the required monthly payment, and any pre-payment penalties or balloon payments the buyer would have to pay. The first page also summarizes the total closing costs and indicates how much cash the buyer will need to close. With these basic terms all in one place, a buyer can easily compare loans.

The second page of the Loan Estimate provides the lender’s best estimate for the details of the closing costs. These costs listed include all the things we’ve talked about in previous lessons, and more—loan origination fees, title search fees, attorneys’ fees, appraisal costs, title insurance fees, transfer taxes, recording fees, mortgage insurance premiums—you name it. Just in case there’s something not listed on the form, the form also includes a line labelled “Other.” You get the idea. The lender is supposed to provide the buyer with a good faith estimate of every cost the buyer might incur with the purchase.

The last page provides additional information about the loan, such as whether a home appraisal will be required, whether the lender intends to transfer loan servicing to another entity, whether the lender requires homeowner’s insurance, and what happens if the buyer is late on a payment.

The last page of the Loan Estimate also includes a section called “Comparisons.” This section provides comparisons based on the total loan—not just monthly payments. The Comparisons section tells the buyer how much interest they will pay and how much of the principal they will have paid off by the end of the fifth year.

The Comparisons section also provides the annual percentage rate, or APR. The APR recalculates the interest rate of the loan, including all the fees associated with the loan, such as loan origination fees or points paid for a discount. A loan with a low interest rate might include high fees that result in the buyer paying more over the life of the loan. The APR allows the buyer to compare loan rates with all the costs included.

Finally, the Comparisons include a number called Total Interest Percentage, or TIP, which expresses the total amount of interest the buyer will pay over the life of the loan as a percentage of the amount borrowed. For example, if the buyer borrows $100,000 and pays $56,000 in interest over the life of the loan, the total interest percentage, or TIP would be 56%. The TIP helps borrowers compare loans using the same metrics.

Congress intended these disclosure requirements—the buyer’s toolkit and the loan estimate—to provide the buyer with the understanding and information they need to shop around for loans and lenders. Because the LE (short for loan estimate) includes a good faith estimate of both the loan terms and the closing costs, the buyer is able to compare all the costs of the loans presented by various lenders and select the lender and the closing that is likely to cost them the least.

Congress also intended RESPA to prevent kickbacks and unearned fees. However, Congress recognized consumers might benefit from efficiencies when a lender refers consumers to settlement service providers the lender owns, or when the lender and the provider are both owned by another entity. RESPA calls these interrelated businesses “affiliated business arrangements.” RESPA allows lenders to refer consumers to affiliated settlement service providers, but only if the lender gives the buyer a disclosure called an Affiliated Business Arrangement Disclosure.

In this disclosure, the lender explains how the lender is related to the settlement services provider, explains that using the affiliated provider will benefit the lender, explains all the fees the affiliated provider will charge, and—crucially—explains that the buyer does not need to use the provider. The lender cannot require the buyer to use its affiliated settlement service providers. The buyer needs to know they can shop around and use someone else. The lender is permitted to require the buyer to use a specified attorney, credit reporting agency, or appraiser in order to protect the lender’s interest, but if the lender is requiring a particular attorney, credit agency, or appraiser, the lender must say so on the affiliated business arrangement disclosure form.

RESPA’s other big disclosure requirement is the Closing Disclosure, which the lender must give the buyer at least three days before closing. However, the Closing Disclosure form is so important, we’re going to spend the next lesson talking about it in detail.

Key Terms

Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act (RESPA)

A federal law requiring the disclosure to borrowers of settlement (closing) procedures and costs by means of a pamphlet and forms prescribed by the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development.

30.5 Settlement Statements

Transcript

INTRODUCTION TO SETTLEMENT STATEMENTS AND CLOSING EXPENSES

I mentioned before that one form is so important we are going to spend a whole lesson talking about it. That form is the Closing Disclosure, and this is the lesson we’ll cover it.

The Closing Disclosure—sometimes called the CD—lays out all the finances of the sale. The Closing Disclosure identifies every expense in the deal and shows who paid what. Because the CD describes the entire deal, it may be the most useful document on the closing table. Parties review the Closing Disclosure for details, long after they stop looking at the deed or mortgage.

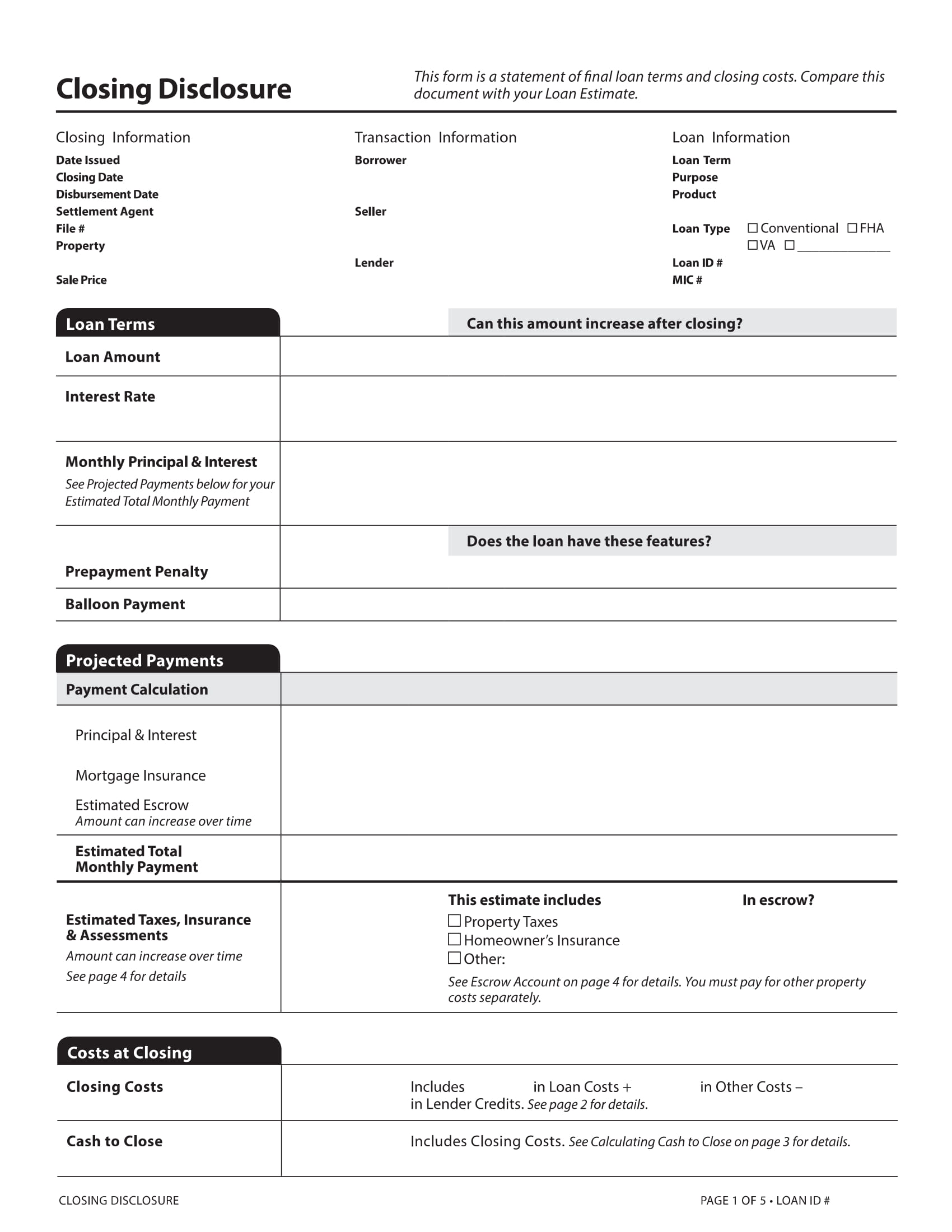

The CD is not only useful—it’s the law. RESPA—the Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act—requires the lender to give the buyer a Closing Disclosure at least three business days before closing. Like the Loan Estimate, every Closing Disclosure you see will look the same—only the names and numbers will change. Look at the sample CD and Loan Estimate you have as we continue. We’re going to explain the CD’s purpose and how it is structured. By the end of this lesson, you’ll understand how to read it.

The Closing Disclosure is relatively new. Congress revised RESPA in 2010, transferring RESPA oversight responsibility to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau—the CFPB. The CFPB created the Closing Disclosure form and required lenders to use the CD form beginning October 3, 2015.

Before October 3, 2015, lenders used a form called the HUD-1 Settlement Statement. The “HUD,” as it is often called, lays out the financial details of the loan and sale, just like the CD does. Federal law still requires the HUD for transactions like equity lines of credit or reverse mortgages, but most residential sales now require the Loan Estimate and Closing Disclosure. Because the CD performs the same task as the HUD, you may still hear people mention the “HUD” or the “Settlement Statement.” Don’t be confused. Chances are they’re talking about the Closing Disclosure.

RESPA requires the lender to provide the buyer with a CD at least three business days before closing. This three-day period allows the buyer to review the numbers and understand the transaction before closing. To meet the three-day rule, the lender will gather all the required numbers and information well before closing—maybe as many as 10 days before closing.

Remember, the lender must provide the CD at least three business days before closing. Not three calendar days, not three weekdays—three business days. In this context, business days means all days except Sundays and federal holidays. This timing issue can lead to some confusion, so let’s take a moment to clarify how it works.

Let’s imagine that Martini is buying a house from Potter, and the Bailey Brothers’ Building and Loan is financing Martini’s purchase. Suppose Martini, Potter, and Bailey Brothers’ schedule the closing for a Thursday in a week without holidays. Counting back three business days from Thursday, we get Wednesday—one day; Tuesday—two days; and Monday—three days. So, by this count, Bailey Brothers has to give Martini the CD by Monday. That’s three calendar days and three business days.

But things change if they schedule closing for Wednesday. Counting back three business days from Wednesday, we get Tuesday—one day; Monday—two days; Sunday—wait, don’t count Sunday because it’s not a business day; and Saturday—three days. In this situation, Bailey Brothers’ has to give Martini the CD by Saturday. That’s three business days, but four calendar days.

If you add a holiday into the mix, additional days appear. For example, suppose Martini, Potter and Bailey Brothers’ chose the Tuesday after Martin Luther King Day. Counting back three business days goes like this: Monday—holiday; Sunday—not a business day; Saturday—one day; Friday—two days; and Thursday--three days. Here, Bailey Brothers would have to provide the CD five calendar days before closing because two of the intervening days are not business days.

Why am I dwelling on this? Because time, as they say, is money. The three-day window can delay the transaction. For example, if some numbers on a Closing Disclosure change by a certain amount, then RESPA requires the lender to give the buyer a new CD and a new three-day waiting period to review the new CD.

Although three days does not sound like a lot of time, if you include a Sunday or a holiday, then the new waiting period can push closing off by a week. Sellers want to get their money and move on. Buyers want to get their house keys and move in. Real estate agents and brokers want to collect their commissions and sell more houses. Last minute delays in closing are frustrating. For this reason, the parties try to provide accurate numbers to avoid triggering delay.

DEBITS AND CREDITS

The Closing Disclosure is all about money—money coming in and out of the transaction. To talk about all that money, we’re going to have to clarify some terms, particularly debits and credits.

These terms are accounting terms, and we use them to monitor accounts. An “account” is any activity or asset you want to keep track of, like your hand-made jewelry business on Etsy, your personal stamp collection, or your checking account.

We keep track of these accounts using debits and credits. In general, we call amounts that flow into an account credits, and we call amounts flowing out of an account debits. Now, that is a broad generalization, and if this were an accounting course, we would talk a lot more about debits and credits. For our purposes, it is enough to think of debits as expenses that cause money to flow out of an account and credits as money flowing into an account.

Debits and credits depend on your point-of-view. One person’s debit is another person’s credit, even when we’re talking about the same thing. A simple example will illustrate this.

Imagine Martini buys Potter’s house for $200,000 cash. Before closing, Martini has an account called “Cash” with $200,000 and an account called “House” with nothing. At closing, he gives $200,000 to Martini, and Martini gives him the deed to the house. From Martini’s perspective, in terms of debits and credits, Martini would record a $200,000 debit in his “Cash” account, but credit his House account with a house.

Now consider Potter’s perspective. Before closing, Potter had $0 in his cash account and a house in his “House” account. After closing, Potter will debit his “House” account by one house, and he will credit his cash account by $200,000. To Potter, the house is a debit; to Martini, it’s a credit. To Martini, the $200,000 is a debit; to Potter, it’s a credit.

Because the accounting varies depending on who you are, the Closing Disclosure tracks the parties’ debits and credits separately, in separate columns. For the buyer, credits will include things like down payments and loaned funds, and the debits will include things like loan costs, appraisal fees, and title search fees. For the seller, credits will include the buyer’s purchase payment, and debits will include things like loan payoffs and outstanding taxes.

At closing, the debits and credits for each party must add up to $0. If the buyer’s total debits exceed his credits, then the buyer must bring money to closing sufficient to pay the debits down to zero. We call this amount the “cash from buyer to close.” Similarly, if the seller’s credit exceeds his debits, then the settlement agent must cut a check to the seller for the excess credits. We call this amount the “cash to seller.” These two items—the cash from buyer and the cash to seller—are usually the items we need to adjust to make the debits and credits for the respective parties add up to zero.

PRORATED ITEMS

To understand some of what happens on the CD, we also need to talk a little about pro-rated items. For many of the expenses on the CD, one party will pay the entire expense on their own. For example, the buyer pays for borrowing money for the transaction, and the seller pays off his own mortgage loan.

However, we incur some expenses over time, but pay for them intermittently. For example, we pay real estate taxes once or twice a year, but those payments cover liabilities incurred over a year. Similarly, interest accrues on a mortgage loan daily, but we only pay the mortgage monthly. Closing rarely happens on a day when these time-based expenses will resolve neatly. We usually have amounts that someone prepaid for the future or accrued expenses that remain unpaid. In these circumstances, we divide the expense, assigning a portion to the seller and a portion to the buyer. We call this process, pro-rating. To explain this idea, let’s return to Martini and Potter.

Imagine that in their town, the property tax year runs from September 1 to August 31, and residents prepay property taxes each year on September 1. Suppose on September 1, Potter pays $1,000 in real estate taxes. Let’s imagine further that Martini and Potter schedule their closing for March 1—midway through the property tax year. The taxes for the period before closing are Potter’s responsibility, but the taxes after closing are Martini’s responsibility. However, Potter prepaid 100% of the taxes for the whole year, but he only bears one-half the responsibility. So, on the Closing Disclosure, Potter will receive a pro-rated credit of $500, representing one-half of the $1,000 in taxes he prepaid. Martini will receive a debit for $500, representing reimbursement to Potter for the one-half of the tax expense Potter pre-paid.

A similar calculation happens with mortgage interest. Mortgage interest accrues daily. If you pay a loan off, the interest ends. Each day, the lender waits to see if you will repay the loan before charging interest. However, most mortgages require payment on the first of each month, with the first payment due one full month after closing. So, if you close on March 18, your first mortgage payment is usually due May 1. But if a closing occurs on March 18, how does the borrower pay the lender for the interest from March 18 to March 31? Trying to include this partial interest in the loan repayment amortization complicates the math, so the buyer generally prepays the interest that will accrue over the end of the closing month at closing as a closing cost. We pro-rate this interest because the interest only accrues over part of the month.

Any item that involves a recurring payment or accrual will usually receive a pro-rated treatment. The most common pro-rated items are things like county taxes, city taxes, water charges, homeowners’ association fees, and condo fees. In general, if you see a recurring expense requiring intermittent payment, a pro-ration may be required.

THE CLOSING DISCLOSURE

So what’s on the Closing Disclosure? Let’s take a little tour. We’ll start at the 20,000-foot view and look closer as we go. The CD has five pages. Always five pages and always the same five pages. Get to know and love them, and you’ll never be confused.

The first page provides a general loan overview for the buyer. The second page details all the closing costs. The third page summarizes the transaction and calculates how much money the buyer must bring at the beginning of closing and how much money the settlement agent must give the seller at the end of closing. The fourth page discloses important information about how the lender will administer the loan. The fifth and final page provides calculations about the loan as a whole, some additional disclosures, and contact information for key players in the transaction, like the lender, the mortgage broker, the real estate brokers, and the settlement agent. That’s the big picture. Let’s swoop in closer.

The first page has four basic sections. The top section identifies the borrower, the seller, the lender, and the settlement agent. It also shows the closing date and describes the kind of loan the borrower is taking, like, for example, a 30-year conventional loan.

The second section, titled “Loan Terms,” describes the major terms of the loan. It shows the loan amount, the interest rate, the monthly payment for interest and principal, and whether the loan includes a prepayment penalty or a balloon payment.

The third section, titled Projected Payments, forecasts the monthly payments the buyer will need to make each month for principal and interest, mortgage insurance, and escrow funds. This section also estimates the monthly cost of taxes, insurance, and assessments.

The fourth section on this page, titled Costs at Closing, summarizes the total closing costs and the cash the buyer will need to bring to closing in order to close. This number is important, because if the buyer does not bring that amount to closing, then the closing cannot happen.

Does this sound a little familiar? Well, maybe it’s because these sections mirror the first page of the Loan Estimate, which we discussed a few lessons back. This mirroring happens by design, not chance. Because the first page of the Loan Estimate and the Closing Disclosure are virtually the same, a buyer can quickly compare the Loan Estimate the lender gave them when they applied for the loan with the Closing Disclosure the lender provides three business days before closing, and see whether any of the numbers have changed. If these numbers have changed significantly, then the buyer can find out why.

The second page of the CD details the closing costs. This page has two major sections, labeled “Loan Costs” and “Other Costs.” The page also has three columns running down its length, labeled Borrower-Paid, Seller-Paid, and Paid by Others. In these columns, the settlement agent will list all the assorted debits to buyer, seller, and others. The Closing Costs page is similar to the second page of the Loan Estimate, but the Loan Estimate only shows the costs to the borrower. The CD shows the costs for both buyer and seller.

The Loan Costs section of the CD details all the costs associated with getting and creating the loan, like origination fees, appraisal fees, or title search fees. Because the buyer is usually the borrower, the expenses in the Loan Costs section are usually debits for the buyer. The seller’s column usually looks empty in the Loan Costs section.

The “Other Costs” section includes costs not related to the loan, like taxes, prepaid expenses, and initial escrow deposits, home inspection fees, commissions to real estate agents or brokers, owner’s title insurance fees, or homeowner’s association fees. In the “other costs” section, the expenses fall across all three columns. The seller’s column gets some expenses (most notably commissions), and the buyer’s column gets others. Every now and then, there’s an expense paid by someone other than the buyer or seller, which is listed in the “Paid by Others” column.

Here on the second page of the CD, the buyer can see all the costs required to close the loan itemized in one place, with a nice total at the bottom of each column showing the total closing costs for both buyer and seller. If the borrower wonders how the closing costs got so high, the buyer can look at this page for a detailed explanation. The “closing costs” amount at the bottom of the first page should equal the “total closing costs” shown at the bottom of the second page.

The third page summarizes the transaction for buyer and seller. The first section, a table called “Calculating Cash to Close,” is for the Borrower. This table figures out how much cash the Buyer must bring to closing by adding up all the closing costs and subtracting any money the borrower has already paid. This table also compares the figures in the Loan Estimate to the figures in the CD and briefly explains any differences between the two.

The second section, called “Summaries of Transactions” shows the buyer’s and the seller’s transaction side by side, listing the debits each owes and the credits each is entitled to. The Borrower’s column shows the amounts the borrower must pay at closing, like the purchase price of the property, the total closing costs, and any adjustments the buyer must pay the seller. Then it shows any amounts paid by or on behalf of the borrower, like down payments, loans, refunds, or amounts the seller didn’t pay but should have. When you subtract the money that has come in, from the money that must go out, you get the cash the buyer needs to bring to closing.

On the seller’s side, you start with the money the seller is entitled to get, like the purchase price of the property and pro-rated payments from the buyer for amounts the seller prepaid. Then, the column lists the items the seller must pay, like commissions and loan payoffs. When you subtract the expenses due from the seller from the amounts due to the seller, you get the net amount the seller must receive at closing. Taken all in all, the second and third page of the Closing Disclosure lays out the entire transaction for buyer and seller in exquisite detail.

The fourth page discloses some important features of the loan that the dollars-and-cents of the first three pages might not reveal. For example, here, the lender discloses whether it will allow someone else to assume the mortgage—to allow someone else to take the borrower’s place in the loan. If the lender can demand early repayment of the loan, the lender must disclose that here as well. If the loan payments will be too low to pay all the interest due in a given month, and the lender will add the unpaid interest to the amount owed, causing the loan amount to grow each month, the lender must tell the buyer here. The fourth page also reminds the buyer that the home is securing the loan and lists the amounts the lender will require the buyer to place in escrow each month.

The last page of the Closing Disclosure provides some other important disclosures. The third page states that the lender must give the buyer a copy of any appraisals at least three days before closing. The third page also tells the buyer whether the buyer will still have liability in the event of a foreclosure. A table, titled “Loan Calculations,” calculates the total amount the buyer will pay if the borrower pays the loan as scheduled. This table also breaks the total number down, showing the amount the borrower borrowed and the total financing cost of the loan. Finally, the Loan Calculations table shows the Annual Percentage Rate actually paid over the life of the loan and the Total Interest Percentage, which is the total interest amount, paid over the life of the loan, expressed as a percentage of the total amount borrowed. These calculations also appear on the Loan Estimate, and the Buyer can easily compare them.

There you have it—the Closing Disclosure form. May its mysteries never mystify you. In the next lesson, we’ll talk about the IRS. Only a little. I promise you.

Key Terms

Credit

A bookkeeping entry on the right side of an account, recording the reduction or elimination of an asset or an expense, or the creation of or addition to a liability or item of equity or revenue.

Debit

That which is due from one person to another.

Proration

Adjustments of interest, taxes, and insurance, etc., on a pro rata basis as of the closing or agreed upon date.

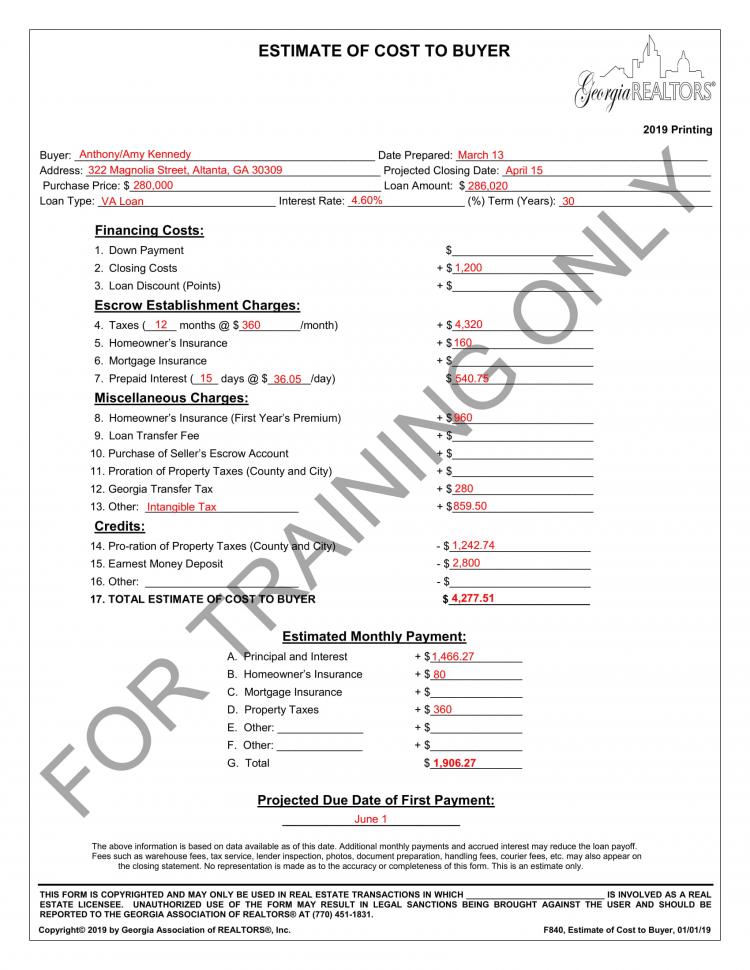

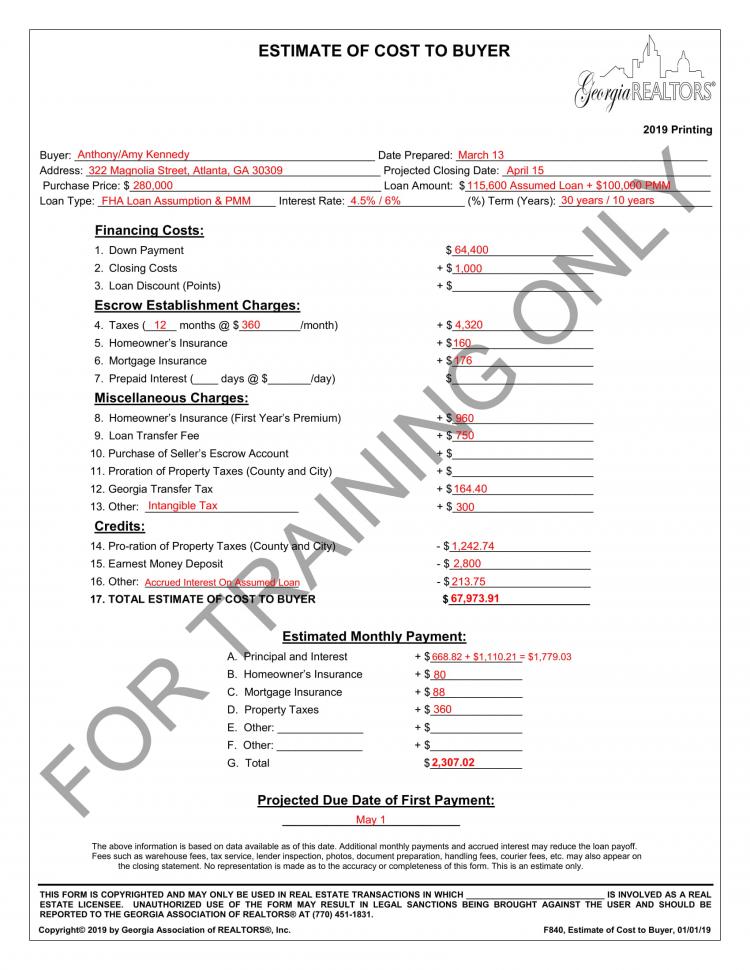

30.5a Closing Disclosure

Please spend a few minutes reviewing the document below.

30.5b Loan Estimate

Please spend a few minutes reviewing the document below.

30.6 Settlement Calculations

Transcript

In this lesson, we will go over several closing costs calculations related to a settlement statement. These calculations will give you a better understanding of how to complete a settlement statement.

Let’s start with a discussion on prorating loan interest at closing.

Mortgage payments are typically paid in arrears (or, in the past). For example, a mortgage payment made on May 1st will be for the month of April. When it comes time to close on a property, the seller will still owe partial interest on their mortgage for the month in which the closing occurs, since they will not make the next mortgage payment. This will be written as a debit to the seller on the closing settlement statement.

From the buyer’s perspective, they will not make a mortgage payment until after one full month of ownership of the property. For example, if the buyer closes on March 15th, their first mortgage payment wouldn’t be until May 1st. The May 1st mortgage payment will include principal and interest paid for the month of April, since the mortgage payment is paid in arrears. For this reason, the buyer is still responsible for paying interest on the loan for the remaining days in March, after the closing occurs. This partial interest payment will also be marked as a debit towards the buyer on the settlement statement.

Let’s go over an example to clarify how this works.

We’ll assume a property closes on April 17th.

The seller was supposed to pay April’s interest as part of the mortgage payment due on May 1st. For that reason, the seller is responsible for paying interest on their mortgage from April 1st to the 17th, or 17 days. The 17 days of interest owed by the seller will be paid at closing and will be marked as a debit to the seller on the settlement statement.

The buyer will not have their first mortgage payment until June 1st. The June 1st payment will include the interest owed for the month of May, but what about the last 13 days in April?

At closing, the buyer will pay the interest for the last 13 days of April, which will be marked as a debit on the settlement statement.

Before we go into specific examples of how to calculate prorated loan interest, we first must learn how to determine how much interest is paid per diem, or per day.

To calculate the amount of interest paid per diem, we must use the following formula:

(Loan Amount x Interest Rate) / 360 days.

It is important to note here that lenders use a 360-day calendar, rather than a 365-day calendar.

Let’s go through a quick example using this formula.

We’ll assume the loan amount is $370,000 at an interest rate of 4.25%.

First, we must multiply $370,000 by 0.0425 (the interest rate expressed as a decimal) to get $15,725. This is the amount paid in interest on an annual basis.

Next, we divide $15,725 by 360 days (remember lenders use a 360-day calendar) to get $43.69 paid in interest each day.

Now, let’s go through an example that may occur at a closing.

The closing date is set for August 12th.

The buyer is obtaining a new mortgage for $260,000 at a 4.5% interest rate.

The seller’s existing mortgage has a loan balance of $92,000 at a 5.25% interest rate.

As stated above, the buyer will own partial interest for the remaining days in August, after the closing occurs. So, how much interest does the buyer owe for the month of August?

First, we determine the per diem interest payment.

This equals $260,000 x 0.045, or $11,700 in annual interest.

Then we divide $11,700 by 360 days to get $32.50 in interest paid per diem.

Next, we determine how many days of interest the buyer is responsible for.

August has 31 days and since the closing is set for August 12th, the buyer will be responsible for 31 days minus 12 days, which equals 19 days of interest.

Next, we determine the total amount of interest due in August.

For this, we simply multiply the per diem amount by the number of days, which equals $32.50 multiplied by 19 days to get $617.50.

The buyer will be debited $617.50 on the settlement statement.

On the other side of the transaction, the seller is also responsible for paying partial interest for the month of August. So, how much does the seller owe?

Just like with the buyer, we first determine the per diem interest payment.

This will equal the loan balance of $92,000 multiplied by 0.0525, which gets us $4,830 in annual interest. We then divide $4,830 by 360 days to get $13.42 in per diem interest.

Next, we determine how many days of interest the seller is responsible for.

The seller is responsible for the first 12 days of August since they still own the property through the closing date.

Finally, we determine the total amount of interest due in August by multiplying $13.42 by 12 days to get $161.04. The seller will be debited $161.04 on the settlement statement.

Next, let’s discuss prorating annual property taxes.

Property taxes are due on specific dates each year; however, even if taxes are due on November 15th, for example, they count toward the current calendar year (January 1 – December 31).

Because of this, there will be times when the property taxes have not yet been paid by the closing date. In this case, the buyer will have to pay the full years’ worth of taxes after closing and therefore be reimbursed by the seller for the days leading up to (and including) the closing date. In other words, the buyer will receive a credit from the seller and the seller will be debited their portion of the property taxes.

On the other side, if the property taxes for the year were already paid prior to closing, the seller will be credited the amount paid in property taxes through the closing date, while the buyer will be debited the same amount.

Let’s go through an example to see how this works.

The closing date is set for April 20th; however, the property taxes are not due until May 15th. The annual property taxes due are $3,200.

Since the property taxes have not been paid by the closing date, the buyer will be responsible for paying the full years’ taxes on May 15th. For this reason, the buyer must be reimbursed by the seller for the days between January 1st and the closing date. This is because the seller is still responsible for paying the property taxes while they owned the property.

Let’s go through the steps to determine the amount credited to the buyer.

First, we must calculate the amount of taxes paid per diem.

To find this, you must take the annual tax bill and divide it by 365 days.

This equals $3,200 divided by 365, or $8.7671 per diem.

Next, we calculate the number of days starting with January 1st and ending at the closing date of April 20th.

January has 31 days, February has 28 days, March has 31 days, and April has 20 days until the closing date. That’s a total of 110 days.

Finally, we multiply the number of days between January 1st and the closing date by the per diem amount. This equals 110 days multiplied by $8.7671, or $964.38.

Since the taxes will be paid after the closing date, the buyer will receive a credit for $964.38 on the settlement statement. The seller will be debited the same amount.

Let’s go over one more example, this time assuming the taxes were paid prior to the closing date.

The closing date is set for August 5th. The property taxes were paid on January 15th in the amount of $5,600.

Since the property taxes have already been paid by the seller at the time of closing, the seller must be reimbursed by the buyer from the day after the closing date to the end of the year.

To determine how much the seller will be reimbursed, we must first calculate the amount of taxes paid per diem. This equals $5,600 divided by 365 days, or $15.3425 per diem.

Next, we calculate the number of days from the closing date until the end of the year.

August will have 26 days, September will have 30 days, October will have 31 days, November will have 30 days and December will have 31 days. This gives us a total of 148 days.

Finally, we multiply the number of days between the closing date and the end of the year by the per diem amount. This equals 148 days multiplied by $15.3425, or $2,270.69.

The buyer will have to reimburse the seller in the amount of $2,270.69 for the days after closing, since they will be the owner of the property.

The buyer will be debited $2,270.69 on the settlement statement, while the seller will receive a credit for the same amount.

Next, let’s go over how to prorate hazard insurance premiums.

Prorating insurance is different from property taxes in that insurance premiums renew on the date the policy was issued, which is usually the closing date for the existing owner.

For example, if a homeowner purchased their insurance policy on February 15th, the policy will end the following year on February 14th.

Hazard insurance is always paid in advance and will be marked as a credit to the seller at closing.

The seller must be reimbursed by the insurance company for the days after closing and until their policy renewal date.

Let’s go through an example.

The closing date is set for October 12th. The seller pays $1,200 per year in hazard insurance, with an end date of January 15th. To determine how much the seller will be reimbursed by the insurance company, we must take the following steps.

First, we calculate the amount of insurance paid per diem. This equals $1,200 divided by 365 days, which gives us $3.2877 per diem.

Next, we calculate the number of prorated days beginning with the day after closing and ending with the last day of the policy. There are 19 days remaining in October, November has 30 days, December has 31 days and January will have 15 days until the closing. This gives us a total of 95 days.

Finally, we multiply the number of prorated days by the per diem amount. This equals 95 days multiplied by $3.2877, which gives us $312.33.

The seller will be credited $312.33 on the settlement statement. In other words, the seller’s insurance company will reimburse the seller $312.33 for the days they pre-paid but no longer owned the property.

Next, let’s discuss how to prorate rental income.

In income producing properties, the rental income collected each month must be prorated between the buyer and seller at closing.

Rental income is typically collected in advance for the upcoming month.

When the rental property is sold, the seller gets to keep the portion of the rent through the closing date, but will credit the buyer for that portion of the monthly rent beyond the closing date.