Chapter 8 - Encumbrances

Learning Objectives

At the completion of this chapter, students will be able to do the following:

1) Provide at least two examples of liens on real property.

2) Provide at least two examples of easements.

8.1 Liens

Transcript

Over the next several lessons, you will learn about various types of encumbrances that can affect real property.

While the word “encumbrance” sounds complex, they are actually extremely common in real estate. Simply put, an encumbrance is a broad term that refers to anything that affects, or places limits on fee simple, title, or the value of real property. Some examples of encumbrances include liens and easements.

In this lesson, we will focus on different types of liens.

A lien is a form of encumbrance that serves to create a security interest in specific, identifiable real property, for payment of the property owner’s debt or other financial obligation.

At its most basic level, you can think of a lien as being a protection for a creditor. When there is a lien on real estate, it means that the lien holder has some claim to (or right to) part of the property’s value.

There are several different types of liens. Liens can be either general or specific, and either voluntary or involuntary. To understand the difference between the two, think of them this way. A “general lien” is a lien on the entire property owned by a debtor. In contrast, a “specific lien” is a lien that is only tied to a specific piece of a debtor’s property.

Now, let’s explore voluntary property liens.

As the name implies, a voluntary property lien is one that the property owner willingly agrees to accept, or that is the result of the property owner’s voluntary action.

The most common type of lien is a voluntary property lien known as a mortgage lien. When someone wants to borrow money from a bank or mortgage lender to finance the purchase of real estate, the mortgage lender has a lien against the property equal to the amount of the unpaid mortgage principal and interest.

This is important for banks and mortgage lenders, because they want to be able to protect themselves in the event the borrower (property owner) defaults on the loan. If that happens, the lender should be able to recoup the amount they are still owed for the loan.

Mortgage liens are voluntary in the sense that the property owner agrees to the lien as a condition of being approved to borrow funds to purchase real estate. Of course, if a homebuyer didn’t want to agree to a mortgage lien, he or she could do that, but that also means they wouldn’t be able to borrow the funds needed to purchase real estate. That is to say that mortgage lenders require liens in exchange for lending money.

Mortgage liens are also specific liens, meaning that the lien is only attached to one specific piece of real property. This means that if the borrower defaults and the property is underwater, the lender cannot directly go after the borrower’s other home or other non-real estate assets to make up the difference for what they’re still owed (although they could pursue legal action in the court system.)

Let’s dig into an example of mortgage liens, as it is highly likely you will encounter them on a regular basis when working as a real estate professional:

Jimmy and Kim want to buy a vacation home and they’re going to take out a mortgage to finance 80 percent of the purchase price. As a condition of approving the loan, the lender will record (or file) a mortgage lien with the county where the property is located. Jimmy and Kim agree to this when they sign documents at closing.

The lender creates and files the lien against the vacation home.

After two years, Jimmy and Kim decide to sell their vacation home. Unfortunately, the market has declined, so at closing, the amount they receive is only $1,000 more than what is still owed on their mortgage.

The mortgage lien ensures that the lender will receive the full amount owed first; Jimmy and Kim will receive the $1,000 above the loan balance.

Let’s say that, instead of selling their home, Jimmy and Kim fell on hard times and had to let their vacation home go to foreclosure. In this case, the mortgage lien functions as a security interest, helping to ensure that the bank will be able to recoup the sales proceeds up to the amount they are owed (and any associated foreclosure fees or expenses, as agreed to in the mortgage note.)

So far we have looked at mortgage liens, which are voluntary liens.

Let’s turn now to involuntary liens.

An “involuntary lien” is a lien against property that is filed or recorded and that does not require the consent or approval of the property owner.

There are several types of involuntary liens, including equitable and statutory liens.

An equitable lien is a lien imposed on real property by the court system. Equitable liens can occur when there is a civil or criminal judgment against a property owner. The court may enter and enforce an equitable lien against the property’s value so that the person or organization on the receiving end of the judgment will be more likely to actually receive payment on the judgment.

Equitable liens are also referred to as “judgment liens”. A judgment lien is simply a legal claim on all of the property of a judgment debtor which enables the judgment creditor to have the property sold for payment of the amount of the judgment.

An example might help put this in context:

Let’s look at Jill. Jill is a bookkeeper who was charged with embezzling $500,000 from her employer. After a criminal trial, Jill was found guilty and was convicted in court. The court awarded her former employer a significant judgment against Jill. Unfortunately, Jill doesn’t have any liquid assets. So, the court created an equitable lien against Jill’s assets, including her primary residence and her beach house in order to enforce the judgment order. This type of lien is a general lien, because it is not tied specifically to one asset or piece of real property.

It’s also an involuntary lien, because Jill does not have to agree to it in order for the lien to be enforceable.

A statutory lien is another type of involuntary lien.

“Statutory liens” arise by statutes (laws). Instead of equitable liens, which require a lawsuit or court judgment, a statutory lien is created automatically by law. Some common types of statutory liens include tax liens, landlord’s liens, artisan’s liens, mechanic’s liens, vendor’s liens and warehouseman’s liens.

Several of these are more common than others, so let’s explore mechanic’s liens and tax liens in more detail now.

A mechanic’s lien is a lien created by statute (by law) which exists against real property in favor of persons who have performed work, or furnished materials, for the improvement of the real property.

That definition sounds more confusing than it actually is.

A mechanic’s lien gives a laborer (or someone who supplied material for construction or remodeling) a security interest in the property that benefited from the construction or remodeling project. So, if a property owner doesn’t pay their contractor or building supplier within a specified time period and as agreed, the laborer or supplier can file a specific lien against the property to protect the amount they are owed.

Almost anyone working on construction, or supplying materials for the construction of real property, can file a mechanic’s lien, although the process of doing so can vary widely from state to state.

Mechanic’s liens can be filed by carpenters, laborers, plumbers, electricians, HVAC or mechanical technicians, as well as by architects, civil engineers, lumber yard, electrical and plumbing suppliers and others.

Other names for mechanic’s liens include construction liens, laborer’s liens, material-men’s liens, supplier’s liens, artisan’s liens, and design professional’s liens.

Mechanic’s liens are involuntary, because the property owner does not need to consent to the filing of a mechanic’s lien.)

Here’s an example of a mechanic’s lien in practice:

Bonnie is building a major addition onto her home. She hires and enters into a contract with a general contractor. When the work was finished, Bonnie refused to pay the contractor. The contractor filed a mechanic’s lien so that if Bonnie tried to sell the home before paying him, he would be able to recoup what he’s owed.

Mechanic’s liens can also be used to protect subcontractors. If, in our example, Bonnie did pay the general contractor, but the subcontractors were never paid, they could file mechanic’s liens against the property.

Now, let’s turn to tax liens.

Tax liens are statutory liens too, because they are imposed by law on property to help the IRS, states or local taxing authorities secure the payment of taxes they are owed by the property owner.

Tax liens are also involuntary, because the homeowner (or business owner) does not need to provide consent for the liens to be filed or enforced.

A tax lien is a way for the government to claim part of a property owner’s real estate because of unpaid taxes.

Generally, tax liens can be filed after the IRS or state taxing authority notifies the taxpayer of how much is owed, and the taxpayer doesn’t pay the debt in full when it is due.

Tax liens can be removed when the tax debt has been fully satisfied, although in certain circumstances, the IRS will consider discharging or withdrawing the lien even if the tax debt has not yet been paid in full.

For an example of tax liens in practice, let’s look at Ken and Amy’s situation.

Ken and Amy are both self-employed. Unfortunately, they underestimated the amount of estimated taxes they owed throughout the year. When it came time to file their annual tax return, they found they owed an additional $15,000 in taxes to the IRS, plus an additional $5,000 to their state taxing authority.

Unfortunately, they didn’t have available funds to pay the taxes, although they received notification and a demand for payment from the government. In this case, both the IRS and the state may file tax liens against their property, so that if Ken and Amy sell their home, the government has some security that the taxes will be paid.

In certain circumstances, the government can force a “tax sale” of property to recoup unpaid taxes from property owners.

We have explored a variety of different liens – before we close out this unit, let’s talk about the priority of those liens. Priority is important, because it establishes the order in which liens are given legal precedence or preference, if there are multiple liens on a piece of real property.

The highest priority liens get paid first, and any additional funds remaining (if any) are used to pay the remaining liens. This is why it is so important to have a lien in the highest position possible. Lower priority liens may never be paid if the funds from the sale of the property at foreclosure are not enough.

Generally speaking, property liens have priority in the order in which they were filed (first in time/first in right.). If the owner falls into foreclosure, the liens are paid off based on their priority.

However, there are some exceptions to this rule.

Tax liens generally take the highest priority, no matter when they were filed.

Mortgage liens will then take the next highest priority as lenders want to be in the highest position possible, in order to reduce their risk. Lenders may get to this position by requiring the borrower to close out all existing liens before issuing the loan.

The remaining liens will take priority based on the date they were filed, with the oldest lien taking the highest priority.

Key Terms

Encumbrance

Anything which affects or limits the fee simple title to or value of property, e.g., mortgages or easements.

General Lien

A lien on all the property of a debtor.

Involuntary Lien

A lien imposed against property without consent of an owner.

Judgment Lien

A legal claim on all of the property of a judgment debtor which enables the judgment creditor to have the property sold for payment of the amount of the judgment.

Lien

A form of encumbrance which usually makes specific property security for the payment of a debt or discharge of an obligation.

Mechanic's Lien

A lien created by statute which exists against real property in favor of persons who have performed work or furnished materials for the improvement of the real property.

Priority of Lien

The order in which liens are given legal precedence or preference.

Specific Lien

A lien that attaches to one specific property only.

Tax Lien

A lien imposed by law upon a property to secure the payment of taxes.

Voluntary Lien

Any lien placed on property with consent of, or as a result of, the voluntary act of the owner.

8.2 Deed Restrictions

Transcript

In this lesson, we will learn about another type of encumbrance, called a “deed restriction.”

Simply put, a deed restriction is a limitation in a property deed that dictates how the property may, or may not, be used by the property owner. Explained another way, deed restrictions are provisions in a property’s deed that include rules for the home, and/or for the plot of land a home sits on.

Sometimes deed restrictions are there because a homeowner’s or condo owner’s association put them there. Sometimes the restrictions were added to the deed by a previous property owner, the builder, or the township.

There are different types of deed restrictions – we’ll explore several of them during this lesson. One thing they all have in common is that they are often permanent, and difficult to remove. Deed restrictions “run with the land”, so they will potentially impact everyone whoever buys and resides in that particular piece of property. The only exception to this is a deed restriction that came with an expiration date that has since passed, or one that was struck down by a court ruling.

Anyone considering purchasing a piece of real property that is subject to deed restrictions should fully understand those restrictions. Sometimes, new owners bristle at what they perceive as restrictive rules and requirements for their property. It may be helpful for them to remember that the restrictions are not arbitrary, and that they were put there for a reason.

So, what are common deed restrictions? Let’s explore some real-life scenarios where deed restrictions come into play, and serve a valuable purpose.

1. Restrictions on what homeowners or their tenants can keep in their front yards

Neighborhood associations have a vested interest in trying to keep their property values as high as possible. After all, that benefits everyone. So, it is common to have deed restrictions that prohibit residents from keeping certain large or potentially unsightly (or annoying) items in their front yards or even in their driveways.

Examples of this type of restriction might include:

- Recreational vehicles/motor homes

- Cars that are no longer operational, or cars without valid license plates (which infers that they are not being used by the home’s residents)

- Boats

- Trailers

The idea behind this type of restriction is to prohibit homeowners from effectively turning their yards into junk yards.

2. Restrictions on the main structure itself

For new construction (including if a house is being re-built or extensively remodeled), deed restrictions might limit the number of bedrooms or bathrooms the house can legally include.

Another example is a restriction that says the property may only be used as a single-family dwelling. So, a property owner who wanted to turn the building into separate apartment homes would be prohibited from doing so under that restriction.

The rationale behind this type of restriction is that it may help avoid a situation where sewers or septic tank capacities are overwhelmed.

3. Restrictions about adding structures to the property, or adding on to existing structures

Sometimes deed restrictions limit the types of additions or improvements a homeowner can make to their property. These are often, but not always, found in scenic neighborhoods, where there might be a concern that someone adding a building or structure to their home could obstruct other homeowners’ views and enjoyment of their own properties.

For example, property owners may be restricted from adding additional structures to their property. This may include restrictions against adding more than one garage, adding a workshop, a pole barn, a shed or an “in-law” apartment to their yards.

Before beginning construction, property owners should also ensure they are not running afoul of deed restrictions that prohibit the use of certain types of building materials, or that place restrictions on the size of additions.

Deed restrictions may also put limitations on the type of fencing homeowners can put on their property. For example, if a home is overlooking a lake, a deed restriction might limit the homeowner from establishing a high privacy fence because it could restrict the neighbors’ views of the lake.

As with the restrictions about what people can or cannot keep in their yards, restrictions about additions are designed to protect property values.

4. Business restrictions

A property owner who wants to operate a business out of their home might be prohibited from doing so if the property deed restricts it.

The idea behind this type of restriction is to protect the neighborhood from what could be additional vehicle or foot traffic.

Sometimes, this type of deed restriction specifies that homeowners cannot put up signs in their yards.

Taking the business restriction even further, some deed restrictions may also prevent homeowners from renting out a room in their home for a night at a time – this is a big deal in some neighborhoods now because of the rise in popularity of services like AirBnB and VRBO.

5. Restrictions about how the exterior of the property is maintained or decorated

Deed restrictions could be used to limit the paint (or siding) color homeowners can use, or the color or type of shingles they put on their roofs.

Or, homeowners might find that they are limited by deed restriction when it comes to decorating their home with holiday lights and other décor.

6. Landscaping restrictions

Deed restrictions can also limit the number, and the type, of trees a homeowner can put on their property, or the type and number of trees they are legally allowed to remove from their property.

7. Restrictions on animals

Another fairly common type of deed restriction is a limitation stipulating what kinds of animals are allowed on the property (or what kinds are not allowed there.) Livestock like chicken or sheep are often prohibited. This is, presumably, so neighbors do not have to put up with the smell and noise that can come from farm animals.

Deed restrictions may also include requirements about the types of pets property owners can have on site, and/or the number of pets. For example, property owners may be prohibited from owning venomous snakes or spiders, or from having more than three cats or dogs.

While it may seem like there is no limit to the types of things that can be included in deed restrictions, there are actually some limitations. For example, deed restrictions cannot be used to keep out homeowners of a certain race or those who hold certain religious beliefs.

Sometimes, home buyers and property owners find themselves subject to restrictions that were put in place 100 years ago, and that no longer make sense given changes to the surrounding communities. Or, maybe a restriction was added to the deed by a homeowner’s association that no longer exists and cannot enforce the restriction.

A deed restriction by another name…

Sometimes deed restrictions are referred by the acronym “CC&R”, which stands for covenants, conditions and restrictions. CC&Rs describe the rules that affect property owners within the same subdivision or tract of land, and related to a homeowner’s association or condo owner’s association that was organized for the purpose of operating and maintaining property commonly owned by the individual owners.

A word about homeowners’ and condo owners’ association rules: they are not the same as deed restrictions.

Don’t make the mistake of confusing deed restrictions for homeowners’ or condo owners’ association rules; they are different.

Deed restrictions are contained in a legal document recorded with the county recorder or registrar of titles. Association rules, on the other hand, are controlled and promulgated by the association itself, but are not tied to the land at the county level.

Association rules can be similar to deed restrictions, saying that owners cannot use certain color paint for their front doors, for example. However, when enough homeowners object to the association’s rules, they are easy for the homeowner’s association board to change.

Deed restrictions are difficult, if not impossible, to change. In order to invalidate a deed restriction, a homeowner would need to go to court to get a judge’s ruling on the matter. As you can probably imagine, that process is both time consuming and costly, and there is no guarantee that the judge will rule in the property owner’s favor.

Deed restrictions apply even if they’re not on the most recent deed

It is important to note that deed restrictions stay with the land, even if they are not referenced in a new home buyer’s property deed. Once they are recorded with the county, they apply. A title search can identify whether, and what, deed restrictions apply to a particular piece of real estate.

Key Terms

Covenants, Conditions, and Restrictions (CC&Rs)

The basic rules establishing the rights and obligations of owners of real property within a subdivision or other tract of land in relation to other owners within the same subdivision or tract and in relation to an association of owners organized for the purpose of operating and maintaining property commonly owned by the individual owners.

Deed Restrictions

Limitations in the deed to a property that dictate certain uses that may or may not be made of the property.

8.2a Limitations in the deed to a property that dictate certain uses that may or may not be made of the property.

Transcript

In this lesson, we will explore easements.

An easement is a right, a privilege, or an interest the holder has in real property owned by someone else, limited to a specific purpose. Looked at from the perspective of the property owner, an easement may seem like another type of limitation or restriction on their property.

Another common name for an easement is a “right of way.”

Easements are said to “run with the land,” which means they pass along with ownership rights when property changes hands from one owner to the next.

Let’s look at several common types of easements you may encounter when you are working as a real estate professional.

At a high level, the two categories of easements are “Easements in Gross” and “Easements Appurtenant.”

An Easement in Gross benefits an individual, company or other legal entity. Utility companies and railroads are examples of two types of legal entities that often hold easements in gross over real property.

For example, if XYZ Power Company needs to extend power to a new subdivision that is being built on the edge of town, they may be granted an easement in gross over Jack’s land so they can run power lines across his property, in order to reach the new subdivision.

With Easements in Gross, transferring the property from one owner to another does not terminate the easement. However, the holder of the Easement may not transfer its rights to someone else without the property owner’s consent.

In our example earlier, XYZ Power Company needed an easement over property owned by Jack, in order to run power lines over the edge of Jack’s property. If Jack sells his property to Sally, the easement will still affect her rights – selling or transferring the property from Jack to Sally did not terminate the easement. However, if XYZ Power Company wants to transfer its easement rights to another person or company, Jack (or subsequent owners) would need to agree to such a transfer. Of course, the original easement may have provided that XYZ Power Company’s rights would transfer to successor companies, so it may not be necessary to get landowner approval in every case, if XYZ Power Company changes hands.

Any easement that is not an Easement in Gross is called an “Easement Appurtenant.” Instead of benefitting an individual or a legal entity like Easements in Gross do, an Easement Appurtenant benefits another parcel of real property.

The property that is subject to the easement is known as the “Servient Tenement” (or “Servient Estate”), and the parcel of property that benefits from the Easement Appurtenant is known as the “Dominant Tenement” (or “Dominant Estate.”)

Easements appurtenant typically transfer automatically when the dominant estate is transferred. That is to say, the rights granted by the easement appurtenant transfer to the new owners of the dominant estate.

Let’s look at another example: Cindy grants David an easement over her property so he can access a public beach conveniently by crossing Cindy’s land. So, David has the dominant estate (the rights granted under the easement), and Cindy’s land is the servient estate – the property that is subject to the easement.

Once the easement has been agreed to and created, it will transfer automatically to future owners of the dominant estate (David’s parcel.) So, if Cindy sells her land to Tom, the easement will still allow David access to the beach by crossing Tom’s land – he still owns the dominant estate, and Cindy’s parcel (now Tom’s parcel) is still the servient estate.

If David subsequently sells his land to Gina, she will now have the right to cross Tom’s land in order to access the beach, because she is the new owner of the dominant estate.

So far, we have learned that easements are either classified as “Easements in Gross” or “Easements Appurtenant.”

Easements Appurtenant can be further classified as either “Negative Easements” or “Affirmative Easements.” Most easements are affirmative. However, it is still important to understand the distinction.

An affirmative easement allows the dominant tenement to physically cross the servient estate. In our last example, David held an affirmative easement, which allowed him to cross Cindy’s property to access the beach.

In contrast, a negative easement does not allow the dominant tenement to enter the servient estate. Instead, a negative easement includes the right to restrict some type of activity on, or use of, the servient tenement. For example, an easement for light and air, or for a particular view, would be a negative easement.

Let’s look at the case of Maria, a homeowner who has a fantastic view of the mountains nearby. John owns the parcel of land adjacent to Maria, between her parcel and the mountains. A negative easement could prevent John, and future owners of his property, from building another story onto his house, because building higher would obstruct Maria’s view of the mountains.

Now that you know what easements are, let’s spend a few moments exploring some of the different ways easements can be created.

Easements can be created in writing. In fact, the most common way to create an easement is by written agreement between the parties.

In the case of an Easement in Gross, the parties are the property owner and the individual or legal entity that will benefit from the easement (like XYZ Power Company in our earlier example.)

In the case of an easement appurtenant, the parties to the written agreement are the property owners of the dominant estate and of the servient estate. In our example of the easement allowing for easy access to the public beach, the parties were Cindy – the owner of the servient estate – and David, who owned the right to cross Cindy’s land.

So, why might property owners decide to agree to create an easement? We have already looked at a couple of situations, but there are many other scenarios that could give rise to an easement.

Here are some specific types of easements created for different reasons, and the ways those easements are created:

First, some easements are easements by necessity. Easements by necessity are created by an agreement between property owners when one parcel of land would not have access to a public road without an easement. In these situations, an easement by necessity can give the dominant estate owner access over adjacent land included in the servient estate. An easement by necessity would be created if crossing the servient estate’s land was absolutely necessary to reach the landlocked parcel, and there was an original intent to provide the lot with access.

For example, if Jane owns a piece of land that is surrounded on all sides by land owned by her neighbor Tom, and she has no other way to access any public roads, an easement by necessity would give Jane the right to cross Tom’s land for the purpose of getting to and from the public road.

Property owners may also agree to create an easement by grant. This is a written agreement between the two property owners, expressly transferring the easement to another party.

Let’s use our previous example, but change it up a bit. Let’s say Jane owns a parcel of land that is surrounded on all sides by land that Tom owns, but there is already a public road cutting through the property giving her access to come and go from her property.

However, let’s assume that Jane doesn’t like going that direction, because it isn’t convenient for her. She and Tom might agree that, in exchange for a one-time payment, Tom would grant an easement allowing for ingress and egress through his property. In this case, an easement is not absolutely necessary, because there is already a public road providing access to Jane’s parcel. But, the parties agreed between themselves to create a separate easement for convenience.

While most easements are created by written agreement, it is also possible to create implied easements in a couple of different scenarios.

One of those types of implied easements is known as an easement by prescription. When the dominant estate has used the servient estate property in a hostile, continuous and open manner for a number of years (as prescribed by state law), an implied easement is created through adverse possession.

An easement by implication is an easement that was not created by express statements between the parties. Instead, an easement by implication arises because of surrounding circumstances that imply or dictate that the parties must have intended to create an easement.

Let’s look at an example that might help clarify easements by prescription.

Ann and Bob own lots that are adjacent to one another. For 16 years, Bob has been planting and tending to a garden. That garden extended six feet into Ann’s property. Bob and Ann live in a state where the law says that implied easements exist after 15 years of hostile, continuous and open use. Assuming Ann never granted Bob explicit permission to garden, an implied easement would exist.

Finally, an easement by condemnation can occur when the government, or a governmental agency, exercises its eminent domain rights over real property. Eminent domain allows the government to condemn a portion (or all) of a property owner’s land for the public good.

One example of an easement by condemnation would be the government using its eminent domain powers to build a public highway that crosses a private property owner’s parcel.

Now that we have explored various types of easements and have discussed how easements are created, let’s spend a few moments talking about how easements end. As mentioned earlier, easements “run with the land.” That means that if a new property owner acquires either the dominant estate or the servient estate that is a party to an easement appurtenant, he or she will also acquire the rights or limitations of that easement.

Although they run with the land, that does not mean that easements can never be terminated. Easements can be terminated in a few different ways:

1. The dominant estate holder could choose to release the easement in writing.

2. An easement could also be terminated when the dominant and servient estates are combined, so the need for an easement is no longer present. For example, if a landlocked parcel is acquired by the person who owns the surrounding lands and the two parcels are combined, there will no longer be a need for an easement by necessity.

3. The easement owner abandons the easement. That is to say, he or she doesn’t use it any longer. The time period for abandonment will be spelled out by state statute.

4. Finally, an easement can be terminated when the purpose of the easement no longer exists. For example, if a parcel is no longer landlocked, an easement by necessity would cease to exist.

Key Terms

Dominant Tenement

A parcel of real property that has an easement over another piece of property (the servient estate).

Easement

A right, privilege or interest limited to a specific purpose which one party has in the land of another.

Easement Appurtenant

An easement that benefits the dominant estate and “runs with the land”. In other words, an easement appurtenant generally transfers automatically when the dominant estate is transferred.

Easement by Condemnation

An easement created by the government or government agency that has exercised its right under eminent domain.

Easement by Grant

The creation of an easement by one party expressly transferring the easement to another party.

Easement by Implication

An easement that is not created by express statements between the parties; but as a result of surrounding circumstances that dictate that an easement must have been intended by the parties.

Easement by Necessity

Parcels without access to a public way may have an easement of access over adjacent land if crossing that land is absolutely necessary to reach the landlocked parcel and there has been some original intent to provide the lot with access.

Easement by Prescription

Implied easements granted after the dominant estate has used the property in a hostile, continuous, and open manner for a statutorily prescribed number of years.

Easement in Gross

An easement that benefits an individual or legal entity, rather than a dominant estate.

Servient Tenement

A parcel of real property that is encumbered by an easement of a dominant estate.

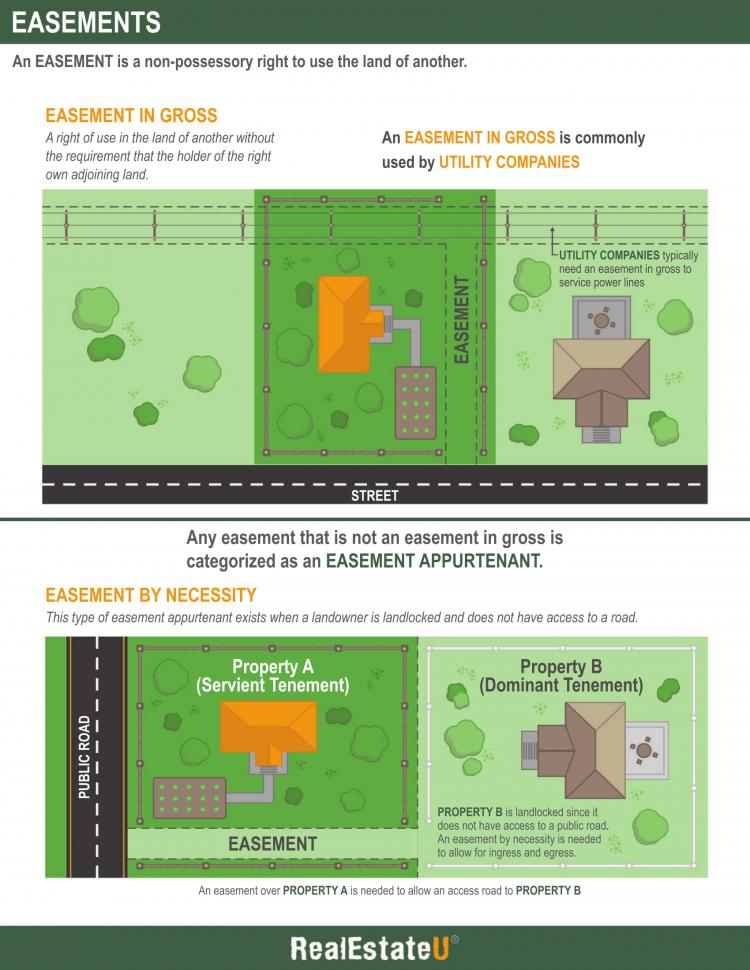

8.3a Easements Infographic

Please spend a few minutes reviewing the Infographic below.

8.4 Encroachments

Transcript

In this lesson, you will learn about encroachments. An encroachment occurs when improvements to real property intrude, unlawfully, onto another’s adjacent property.

In a previous lesson, you learned about easements, where one property owner allows another property owner to use a portion of their property for some purpose. In an encroachment, one property owner is, in effect, using part of a neighbor’s property in an unwanted manner.

In an encroachment, an improvement to one property owner’s parcel intrudes on a neighboring property owner’s parcel. To “intrude” on another parcel of land may mean that a structure is on the land itself; it can also mean that something is hanging over a neighbor’s property.

Encroachments can take several different forms. Let’s look at a few examples to illustrate some common encroachments:

Bill and his friends spend all weekend adding a third garage stall onto his garage, so he has somewhere to keep his motorcycles. When his neighbor, Ann, gets home after being out of town, she notices that the new garage stall actually extends onto her property.

This is a classic example of an encroachment. It does not matter whether or not Bill knew where the property line was when he built the extra garage stall; his garage is an encroachment on Ann’s property.

Similarly, if Ann had built a new deck onto the side of her house, and the edge of the deck hovers over Bill’s yard, she would be encroaching on his property too (whether or not she intended to do so.) It does not matter that the deck isn’t physically in or on the ground on Bill’s side of the property line; the fact that the edge of the deck hovers over his property is enough to create an encroachment.

An encroachment does not need to be an addition onto an existing structure; it can be any type of property improvement.

So, if instead of adding a stall onto his garage, Bill decided to put in a swimming pool and surrounding deck that extended into Ann’s yard, that’s also an encroachment.

Fences are another very common cause of encroachment issues. Here is an example:

John owns rural farmland that borders rural farmland owned by Chuck. Thinking of his neighbor, John decides to put up a fence to keep his farm animals in his pasture, so they won’t wander onto Chuck’s land. He hires some men and builds a fence that extends the entire length of his property. Unfortunately, he misjudged where the property line was, and the fence actually extends six feet into the property owned by his neighbor, Chuck.

Most of the time, like in the examples we just looked at, encroachments are unintentional. That is to say that, when one neighbor’s property improvement intrudes on another neighbor’s land, odds are good that he or she did not realize the improvement was not within property lines.

So, you may be asking yourself, what happens when someone realizes that their neighbor’s property improvements are encroaching on their property?

The answer is, “it depends.”

Sometimes, one neighbor might allege that another neighbor’s property improvement is an encroachment. If the neighbor who made the improvement disputes it and claims that the improvement is entirely within their own property lines, it may be necessary to survey the property lines to determine whether there was really an encroachment or not.

When it is clear that an encroachment occurred, there are a few different possible outcomes.

First, the neighbor whose improvement encroached on neighboring property might be willing or able to remove or change the structure so that the encroachment no longer exists.

It may be difficult in our examples to modify or move the garage stall, deck or swimming pool to remove an encroachment. In the case of the fence that is on a neighbor’s land, the fence could be moved.

If the neighbor who created the encroachment is not willing or able to remove it, he or she may be willing to purchase the encroached-upon land.

A property owner might also decide that they are not really bothered by their neighbor’s encroachment, so they decide just to live with it. This can lead to peaceful neighbor-to-neighbor relationships. But, when the property owner whose property is encroached upon wants to sell their home, they will need to fully disclose the encroachment. Potential buyers need to know about it, and have the opportunity to consider it when making a decision about whether or not to buy the property.

Another option is going to court. However, because this can lead to strained relationships between neighbors, it should be viewed as a last resort. Through a court proceeding, the injured homeowner (the one whose property is encroached upon) may be able to get a “quiet title action” and an “ejectment action” against their neighbor. However, there are no guarantees, and the process can be long. When one neighbor has been improperly using another neighbor’s property for a long time, it is possible that the court could find “adverse possession” and the neighbor whose improvement started the whole thing could prevail.

One possible outcome of taking the encroachment matter to court is an “easement by prescription” (also referred to as a “prescriptive easement.”)

With a prescriptive easement, the court may grant rights to the property owner whose improvement encroached on their neighbor. One common example of this is with a fence built in the wrong location.

For a prescriptive easement to occur, the use of the land has to be open, notorious, hostile and continuous for a period of years. That time period differs from state-to-state.

Let’s look back at our example from earlier.

In that example, John built a fence along what he thought was the property line dividing his rural farmland from land owned by his neighbor, Chuck. In reality, he had the measurements wrong, and built the fence six feet over the property line, on Chuck’s parcel of land.

Let’s assume that after the fence went up, John’s farm animals used all of the land within the fenced-in area, including the part that actually belonged to Chuck, on a daily basis. For the purposes of this example, let’s also assume that John and Chuck live in a state where the statutory period for adverse possession and prescriptive easements is seven years.

Eight years after the fence went up, Chuck learned that the fence was actually encroaching on his property, and he confirmed this with a land survey. He asked John to remove the fence, but John refused.

So, Chuck decided to take his neighbor to court to try to force the removal of the fence.

Does this give rise to a prescriptive easement? If we revisit the requirements for a prescriptive easement, we will see that:

- The use of Chuck’s farmland was hostile – it was used without Chuck’s permission.

- The use of the land enclosed by the border fence was open and notorious - John didn’t try to hide that his animals were grazing on that strip of land.

- John’s animals used the land on a continuous and uninterrupted basis, for longer than the seven years in the state statute.

While the ultimate decision will be up to the court hearing the dispute, it is possible that Chuck will lose, and that the court will grant a prescriptive easement to John for this encroachment.

Key Terms

Encroachment

An unlawful intrusion onto another’s adjacent property by improvements to real property, e.g., a swimming pool built across a property line.

8.4a Encroachments Infographic

Please spend a few minutes reviewing the Infographic below.

8.5 License

Transcript

In this lesson we will explore licenses for real property.

A license is simply special permission to access or use someone else’s real property for a specific purpose. If not for the license, entering the real property could be considered trespassing on private property.

Licenses are actually pretty common - Let’s look at a couple of examples that should help you understand them better.

Example 1: George owns several acres of rural land that include a wooded area and a stream. Every fall, George allows his friends to use his land to hunt, and every spring and summer, his friends are allowed to fish in his stream. George has given his friends “license” rights to use his land for those specific purposes.

Example 2: Kate owns and has restored an historic home in her community, and keeps several rooms in museum-like condition to show what the home was like 100 years ago. She has worked out an agreement with the local school district to allow elementary school students to visit her home for a tour and presentation once a year. The school officials and students are able to enter Kate’s home for these tours and presentations because they have a license to do so.

In a previous lesson, we learned about easements, which give someone else some rights to use a portion of someone’s real property. Remember that easements “run with the land”, which means they are for an indefinite period of time. Easements are also considered to be property rights.

Licenses are a little bit different. Similar to easements, licenses allow someone else to use real property for a specific purpose. However, licenses can be terminated or canceled. A license is also not considered a property right. Instead, a license is merely permission given to the licensee(s) to enter real property for a certain purpose.

Licenses do not need to be in writing; they can be created by verbal agreement. A verbal easement is considered a license.

Finally, it is important to understand that a license to use someone else’s property for a specific purpose is personal to the licensee, meaning that the right is non-transferable, unless the property owner agrees to do so. Licenses also automatically terminate when the real property is sold.

So, let’s look back at our first example, where George had given his friends the right to use his property to hunt and fish. If George sells his property to one of his friends, Dan, the rights of his other friends to hunt and fish on that land end. Dan may decide to grant his friends similar license rights, but that’s completely up to him.

Similarly, if Kate in our second example sells her historic home, the license rights the school district had automatically terminate at closing. The school district would need to try to work something out with the new property owner if they wanted to continue offering students tours of the home.

Key Terms

COPYRIGHTED CONTENT:

This content is owned by Real Estate U Online LLC. Commercial reproduction, distribution or transmission of any part or parts of this content or any information contained therein by any means whatsoever without the prior written permission of the Real Estate U Online LLC is not permitted.

RealEstateU® is a registered trademark owned exclusively by Real Estate U Online LLC in the United States and other jurisdictions.